While the ancient history of Egypt is both rich and well documented, western interest in the nation of pharoes began primarily with the conquests of Alexander the Great. By the time of Alexander, Persian influence had taken control of Egypt and the power of the eastern nation didn't escape his notice.

In order to finance his coming expeditions, Alexander crossed first to Egypt, crushing what little Persian resistance there was. Taking control with relative ease, and being welcomed for his deliverance from Persian rule, Alexander abruptly altered Egyptian culture in a way that would last for the next 900 years.

He first founded the city of Alexandria to act as a Greek-style seat of government for the Nile nation. Many Macedonian and Hellenistic supporters were appointed to various positions of power, and a unique social structure of ethnicities began to develop.

Greeks and Macedonians occupied the elite status, of which native Egyptians had little to no ability or interest in joining, while they occupied the common classes. Occupying the lower tiers were other outside cultures such as Jews, Nubians and other neighbors.

After the death of Alexander in 323 BC, his conquests began to crumble into factional kingdoms. In Egypt, the Macedonian general Ptolemy I Soter (Saviour) eventually took the throne. He established a dynasty that would last 300 years, until Cleopatra and the age of Caesar. In this time, a successive line of Ptolemic Kings of Macedonian descent ruled Egypt, with varying degrees of success.

The early Ptolemies exanded Egyptian and Macedonian influence in the region through various conquests of neighboring territories. Immense wealth was accumulated in the process, and Egypt was slowly becoming the power it once was. The Ptolemies also wisely adopted many Egyptian customs while encouraging Greek Hellenism to prosper.

By the end of the Ptolemy dyansty, the rulers of Egypt were as much Egyptian in culture as they were Macedonian in ethnicity.

Roman contact with the Egyptian state began most likely in the 3rd century BC. Because of Egypt's Macedonian ties, there was certainly some diplomacy between the two during the Macedonian Wars against Philip V and his heir, Perseus. During the related Syrian War, Philip and the Seleucid King, Antiochus III, formed an alliance to wrestle away Egyptian concerns in the region.

Pressed by this alliance, the Egyptians turned to the growing Mediterranean power of Rome in an alliance of their own. Roman victory assured Egypt its continued independence, but closer ties to Rome would eventually turn against them.

The late Ptolemy dynasty did little to ensure Egyptian stability. The rise of several infant kings, with rule by appointed regents, was the source of political and civil strife on a near routine basis. By the 1st century BC, the former great Nile power was becoming more and more a protectorate of Rome.

Due to its inability to govern effectively and efficiently, it fell upon Rome to act as mediator on several occasions. By the time of the eastern campaigns of Pompey in the 60's BC, Rome had taken at least nominal control of much of Alexander's former conquests.

Influence in the Hellenistic east now belonged to Rome, and Egypt's star was waning. In 58 BC, Ptolemy XII Auletes was driven out of his kingdom by a mob in Alexandria, and the Romans were forced to step in again. The first triumvirate of Julius Caesar, Pompey and Crassus restored him to power shorly after but, in 51 BC, the king died.

His death left the kingdom to the 10 year old Ptolemy XIII and his 17 year old sister, Cleopatra VII. The husband and wife siblings - as was the custom in both ancient and Ptolemic Egypt - ruled jointly, but as rivals. The struggle for Egyptian power would soon bring the direct focus of the now supremely powerful Roman Empire.

The civil wars between Caesar, Pompey and the Republican Senators brought Egypt front and center into the conflict. After the battle of Pharsalus in 48 BC, in which Caesar was the victor, Pompey fled to Egypt hoping for safe passage.

The rival Egyptian rulers were in the middle of their own pitched effort for ultimate power, and the result would be disastrous for Pompey. Attempting to win favor from Caesar in his own civil efforts, Ptolemy and his regent Potheinus, had Pompey killed and beheaded when he arrived.

Knowing little of Caesar's famous clemency towards his enemies, they presented the head to him as a gift. Ancient reports suggest a variety of reactions, but all clearly relate Caesar's anger and disappointment by this act. Unwittingly, Ptolemy XIII pushed Caesar into the camp of Cleopatra, and his reign was to be short lived as a consequence.

Caesar met with Cleopatra, and an historic affair blossomed. He soon gave full support to her bid for the throne against her brother and husband, and a civil war erupted in the streets of Alexandria. With only a nominal force, Caesar was hard pressed against Ptolemy, but eventually prevailed. In the fighting that ensued, Ptolemy XIII was killed and the Great Library of Alexandria sustained considerable, but repairable, damage.

While Caesar and Cleopatra continued their affair, resulting in the birth of a son, Caesarion, Cleopatra's even younger brother, Ptolemy XIV, rose to rule with Cleopatra. She later accompanied Caesar to Rome, where she became more in tune to the political environments and made contact with Caesar's Legate, Marcus Antonius.

With Caesar's murder in 44 BC, Cleopatra murdered her brother and elevated her son Caesarion to the position of King. She next attached herself with what appeared to be the next great Roman power in Antony, but it was to be a fateful decision.

Caesar's true heir, Octavian, eventually came to prominence, and more Roman civil war was to come. First working together with Octavian to eliminate Caesar's assassins, the two eventually split. At the battle of Actium in 31 BC, Octavian defeated the forces of Antonius and would head to Egypt. As victory for Octavian closed in, both Antony and Cleopatra committed suicide in 30 BC, and Egypt fell permanently into Roman control for the next 700 years.

Octavian had another motive for his invasion of Egypt, however. Cleopatra had propped her son Caesarion up as the true heir of Caesar, and Octavian was forced to react. If there was any doubt over whether the boy was really Caesar's son, Octavian ended the potential trouble by having him killed.

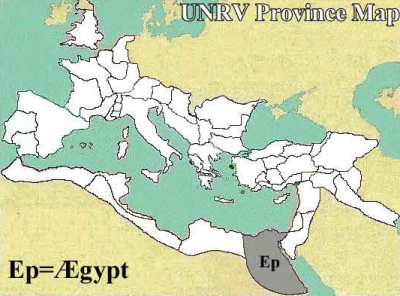

Egypt was set up as a Roman province with a unique difference from other provinces. With all of its great wealth Octavian, soon to be emperor Augustus, kept the province as his personal hereditary property, in which the Senate had no jursidiction at all. While Roman administration would follow in the Imperial period under appointed Prefects, many Greeks continued to staff important administrative funtions.

The Romans also followed the Ptolemy example and did little to alter Egyptian customs, and Greek influence continued to flourish. While the Egyptian gods were adopted into Roman culture, the successive emperors did gradually introduce Imperial cult worship.

Egypt flourished under Roman rule and the region prospered. Factional dissent between Greeks and Jews was a recurring issue, but relative peace reigned. Trajan suppressed a Jewish revolt, but his successor, Hadrian, returned the region to a relative calm.

Opressive taxation later led to a general revolt of the Egyptian natives that lasted several years, and the revolt of Avidius Cassius under the reign of Marcus Aurelius led to general disorder in the east. The emergence of Christianity in ancient Rome also played a part in general disturbances from the 2nd century AD onwards, but Egypt, for the most part, was a peaceful and steady Roman province.

Roman Legions in Egypt

From the beginning of Roman rule, two legions occupied the province. Legio II Cyrenaica garrisoned Alexandria until 106 BC when Legio II Traiana Fortis replaced it. Legio XXII Deiotariana also garrisoned Alexandria until the mid 1st century AD, but it seems to have been destroyed in the Judaean Revolt of Simon ben Kosiba.

Legio II Traiana Fortis garrisoned Alexandria and monitored Egypt at least until the 5th century AD. At this point, the administration of the western Roman empire collapsed and the province continued under Byzantine or Romanion rule until the 7th century AD.

Economy

The economy of Egypt was chiefly agricultural, as the Nile valley was (and is), extremely fertile. Vast amounts of grain and other consumables were regularly exported. Textile manufacturing, especially clothing, seems to have been a key industry as well. Additionally, Papyrus and its end products, such as paper, were a key contribution to the Roman world.

A Brief History of Egypt

Archaic Period

The incredibly fertile plains of the Nile river encouraged settlement of Neolithic communities. From these communities arose (circa 5000 BC) the villages and towns that would form the regional districts of Egyptian history.

These districts were later called "nomes" by the Greeks. The nomes were united broadly in culture, but each was ruled separately by what amounted to a tribal chieftain. Each nome also seemed to have its own tutelary god, for whom the tribal chieftain was considered the sacral king.

The basis of Egyptian religion and government, and the almost total lack of distinction between them, was already lain.

Sometime before 3000 BC the nomes around the Delta region of the Nile, which entered into the Mediterranean, were united into what was called the Red land. Similarly, the nomes south of the Delta were united into the White Land.

Over the course of a few generations, kings from the south established control over the north. Egypt was united as the Two Lands around 2700 BC, with the capital at Memphis. The Egyptians also referred to their land as "Kemet," meaning "Black Land", after the color of the fertile silt of the Nile River.

Old Kingdom

Within several generations of the Unification of the Red and White Lands, Egypt became a highly centralized state, united by a god-king and an imperial bureaucracy. The King was in essence a god on earth, and the chief mediator between humanity and the higher gods of the heavens. This was much like the archaic nome chieftains and their tutelary demons, but on a much grander scale.

The Kings ordered construction of pyramids - specialized burial chambers from whence it was believed their souls would ascend to the heavens and reside with the gods. At this point in history, eternal life was considered the province of the King only.

Beneath the king were his priests, the nobles of the court, the local notables in the nomes, the scribes and other staff of the bureaucracy. A small part-time army was retained, but Egypt's vast deserts helped defend the country from outsiders.

The remaining 80% of the population were serfs, who spent three months of the year farming the Nile. The rest of the year they were conscripted by the State for various building projects (the Biblical account of foreign slaves constructing pyramids is not supported by history or archaeology).

Egypt traded with some of her neighbors, and occasionally went to war.

First Intermediate period

The God-Kings of the Old Kingdom so lavishly built their burial chambers that it actually placed a severe strain on the economy. Furthermore, the nobles and the priests were wresting power and money away from the central court. The central government at Memphis collapsed circa 2180 BCE. The local notables staged civil war for the throne. In the chaos that resulted, Asiatic nomads infiltrated the country. Everywhere there was chaos, followed by famine and disease.

The illusion of an all-powerful God-King ruling timelessly over Egypt was shattered. People no longer felt that the King alone was entitled to eternal life or protection of the gods. "The Democratization of the Afterlife" began in this phase, in which all those who submitted to such venerable deities as Aset (Isis) and Wesir (Osiris) could be granted eternal life.

This was one of the most profound moments in the evolution of religious thought, exerting a strong influence on Paganism ever since, and providing fertile ground for the later Christian religion to follow.

Middle Kingdom

The chaos gradually subsided, and a new line of Kings emerged around 1991 BC. It-Towy became the political capital, and Thebes the chief religious city. The powers of the nobles were curtailed by the central court, and a new middle class of skilled laborers and traders emerges to replace them.

However, about this time, the king came increasingly to share power with his deputy, called the vizier, who would later become a force in politics in his own right.

On the foreign front, Egypt re-initiated trading relations and military campaigns to regain the international status it had lost in the previous anarchy. It was during this timeframe that Egypt made contact with Minos, the proto-Hellenic civilization.

On the domestic front, the new kings began again to order the construction of pyramids and other burial chambers, despite the fact that their economic burden had contributed to the social collapse of the previous era.

Second Intermediate Period

By 1786 BC, Egypt had again fallen into chaos. A series of weak kings came to the throne. During this period the vizier, the kings deputy, may have been the actual power behind the throne. Rival pretenders to the throne established separate dynasties.

With the country weakened, a group of Asiatic invaders called the Hyksos gradually infiltrated the country. They took over the North. The South was not conquered, but had to pay taxes in tribute.

Later Egyptians would say the Hyksos were cruel, malicious tyrants, although the archaeological records do not bear this out. In any event, the Egyptian psyche was so disturbed by this conquest that they grew increasingly xenophobic. Rulers from the religious center of Thebes in the south organized a revolt and expelled the Hyksos back to west Asia.

New Kingdom

The Theban princes established themselves as the new rulers of Egypt around 1570 BC. The mood of Egypt had changed. A once generally peaceful people were altered by the Hyksos invasion. They grew increasingly warlike and xenophobic, and desired overseas empire to defend themselves and increase their status.

The Thebans used the military lessons fighting the Hyksos to establish Egypt's first professional army and conquered parts of west Asia. The military became the second most important institution in the New Kingdom.

By now, the most important institution was the clergy. The Thebans attributed their success to their chief god, Amun. The Egyptians, already a deeply religious people, became all the more so after the Hyksos were repelled. Amun, the Theban god of Winds, was associated with Re, the Memphis solar god of the Old Kingdom.

This new "Amen-Re" was regarded as an all-powerful creator and warrior deity, the patron of the New Kingdom. The Theban priests of Amen-Re became the powers behind the throne as they confirmed the right of the king to rule. The priesthood also came to exercise considerable influence over the New Kingdom's burgeoning economy.

In an effort to wrest political and religious authority from the priesthood and return it to the monarchy, a king by the name of Amenhotep revolted. Amenhotep denied the existence of Amen-Re, and indeed all other gods. According to him, the only god was Aten, the sun disk, and he was the high priest of this one true god.

Amenhotep renamed himself Akhenaten ("servant of Aten"). He closed all the temples and constructed a new capitol around his solar monotheism. Not only the priests but the people at large were scandalized. Once he died, the Theban priests again took control. The cults of the old gods were restored, and it would be centuries before monotheism was again inflicted upon the population.

Bolstered by a strong military and a feeling of religious patriotism, the Egyptians of the New Kingdom successfully repelled an invasion of the Sea Peoples. The Sea Peoples were a mysterious race of marauders who had managed to destabilize other parts of the Mediterranean.

The New Kingdom finally abandoned the practice of pyramid building. Instead, they buried kings in rock-cut tombs. It was in such a tomb where Tutankhamun was famously discovered.

Third Intermediate Period

Egypt reached the height of power in the New Kingdom that it would never recover. Around 1089 BC, the Theban princes took full control of the south of the country, leaving the monarchy with the north. The country was divided, and the monarchy of the north was weak.

Kings from Libya and then from Nubia took over parts of Egypt. Foreign ruled Egypt came into conflict with the new power in the Ancient world, Assyria. The Assyrians destroyed Memphis and placed puppet rulers in parts of Egypt.

Late Period

The Egyptians gradually regained control of their country from all foreign influences, but their international power and overseas empire was ruined. The kings could only retain control by hiring large numbers of mercenaries, who were increasingly Greek.

At this time Assyria fell to Babylon, which in turn fell to Persia. Persia then subjected Egypt to foreign control again. Xerxes was considered a cruel occupier, and when the Persian Empire was overthrown, the Egyptians welcomed their new liberator, though he was also foreign.

Ptolemaic Period

Alexander the Great defeated the Persian Empire. So the legend goes, the Egyptians greeted him with open arms after the oracle of Amun declared him a god on earth and the rightful King of Egypt. Alexander founded Alexandria on the Delta to become the new administrative capitol, and it quickly became the largest port city in the eastern Mediterranean. Alexandria would become a melting pot of Egyptian, Greco-Macedonian, Jewish and other foreign influences.

Alexander died and leadership of Egypt passed to his governor, Ptolemy, who ruled as a Pharaoh. Ptolemy and his successors tried to "modernize" the economic and political administration of Egypt to increase output. This seems to have worked, and the new-found wealth was poured into massive building projects and other affairs of state.

The majority of Egyptians did not benefit, however. The reforms and new economy favored the new regime and its new Greco-Macadonian administrative class. Some Egyptians did move up the social hierarchy by becoming "Greek" in educational terms, but the majority of the populace did not seem able or inclined to trade their culture for that of the occupiers.

Despite the Ptolemaic regime taking a relatively innocuous approach in ruling its Egyptian subjects, there were frequent uprisings by the natives.

Roman and Byzantine Period

The growing shadow of Rome from the Mediterranean coincided with the successive degeneration of the Ptolemaic regime. Under weak rulers, Ptolemaic Egypt watched as Rome devoured the other Hellenistic kingdoms.

Only one Ptolemy was wily enough to meet the Romans at their game, and that was Cleopatra (the VII). After wooing Julius Caesar and using him for internal Egyptian politics, Cleopatra turned to Mark Antony when Caesar was assassinated. After a failed bid for military supremacy of the Roman world, Cleopatra and Antony killed themselves.

Augustus poised himself as Pharaoh and had an equestrian appointed to rule Egypt as a direct imperial territory.

The main Roman interest in Egypt was the grain of the fertile Nile. However, the general economic power of Alexandria, the second largest city in the Empire, was not ignored. The Romans retained the Ptolemaic administration but did introduce Roman legal reforms. The Romans allowed the remains of the Egyptian priesthood to operate so long as they supported the imperial cult.

The Egyptians, for their part, seemed to have largely been apathetic to the Romans, but a few Egyptians (no doubt largely Hellenized by education) did become Senators.

The main event in the Roman rule was the introduction of Christianity. Introduced by Hellenized Jews in Alexandria, it spread quickly to the rest of the population. The Cult of Mary and Jesus was facilitated by its iconographic resemblance to the cult of Isis and Horus, and perhaps to the extent that early Christianity was anti-Roman, it was taken up enthusiastically by the lower urban classes. Coptic was developed as a literary and religious language at this point.

As the Western Empire degraded, the grain supply shifted to the new Eastern capitol of Constantinople. Egypt would become a province of the East, one involved in the various religious controversies of the Byzantines.

Egypt was later conquered by Islam, and its culture completely taken over by the new faith. Not until French and British troops in the nineteenth and twentieth century occupied the country would Egypt and its past be significantly reintroduced into the Western conscious.

Religion Of Egypt

It is important to correct a misconception... the Egyptians were not obsessed with death. That we think so is a function of modern archaeology, which interprets Ancient Egypt through surviving artifacts. Most of the artifacts that have survived are religious and funerary in nature, which colors perceptions of Egyptian mentality.

The religious and funerary buildings so synonymous with Egypt were built to last, and often placed in the desert where they were well preserved by the barren wasteland. By contrast, the items of everyday Egyptian life were built of less durable materials, and much has been lost over the centuries.

Nonetheless, as in most ancient societies, religion infused every aspect of life. Much of the religion was inspired by the striking natural environment of Egypt. The Nile flooded every year, leaving deposits of black silt that made a tiny portion of the land incredibly fertile along the river. The Egyptians named their land the "Black Land" (Kemet) after the life giving silt, in what would otherwise be a wasteland.

By contrast, surrounding Egypt were stretches of barren, red colored sands. Black was the color of life and vitality in Egypt linked to the Nile, while Red was the color of death and danger and deserts. The stark contrast between the creative powers of the Nile and the oblivion of the desert sands would leave a lasting impression on Egyptians.

Egyptian religion has been called "polytheistic", but this is not entirely accurate. While Egypt has hundreds of deities, the vast majority of these are glorified regional spirits; tutelary deities of local tribes that existed long before Egypt was unified.

Most of these deities were not honored outside their immediate cult center, and most Egyptians probably honored few deities aside from their ancestral tutelary god. Only a few deities attained national importance throughout Egypt, and most of these were connected with the royal family.

The extremely localized nature of Egyptian religion frustrates attempts to imbue it with the normal understanding of "polytheism".

Another frustration to the usual polytheistic scheme is the fact that Egyptian deities quite often blended into each other. Sometimes two different deities were nothing more than personifications of a single divine principle.

This was the case with Amon and Re. Amon was a god of the wind, and symbolized the mysterious, hidden forces of creation. Ra, on the other hand, was the ubiquitous power of creation, as represented by the sun. Both deities are nonetheless streams of the creative powers of the universe.

In the New Kingdom period, Amon and Re were combined into a composite deity called Amon-Re to symbolize both the winds and the sun, both the hidden and the plainly visible.

The central concept of Egyptian religion is Ma'at, sometimes symbolized as its own goddess. Ma'at is order, peace and justice on a cosmic scale. It stems from the Egyptian belief that the universe is or should remain essentially static. The Nile had to flood in precisely the right way at precisely the right time every year, or many Egyptians would starve. Thus, the Egyptians came to enshrine the concept of a cosmic stasis.

The champion of Ma'at was the Pharaoh (Nisut). The King was theoretically the chief priest in Egypt, although he could not possibly be everywhere at once, and many minor priests came to exercise most of the daily functions of religion. The King was the mediator between man and gods, and was in some sense divine (he was somehow the living embodiment of Horus, the falcon headed sky god of royalty).

The king upheld the principles of Ma'at and cosmic order. To act against the King was to act against creation and order itself - this religious and political belief helped Egypt remain a remarkably stable and law abiding society throughout most of its long history.

When the king's earthly life had expired, his "soul" would ascend to the realm of the gods and he would take his place in the Sun God's retinue, where he would still be held in a position to defend Egypt. In some epochs, the famous pyramids were constructed to help the King's soul ascend to the gods.

In early Egypt, eternal life was considered the province only of the royalty, as he was the god-king on earth and mediator between humanity and divinity. Only after the social turmoil of the Old Kingdom's collapse did people question this belief and come to see eternal life as the reward for all virtuous people.

The "democratization of the afterlife" came about through a popular myth. Osiris, a good king of Egypt, was murdered by his violent brother, Set. Osiris descended into the underworld to become the god of the dead. Isis, his wife, meanwhile magically conceived a son for Osiris in the form of Horus. Horus, backed by Isis and other gods, fought a long war with Set for the throne of Egypt. Eventually Isis and Horus won the struggle, with Osiris reigning in the afterlife and Horus reigning in Egypt.

Isis, Osiris, and Horus came to be a holy trinity. Because Osiris had conquered death, he could grant eternal afterlife to any virtuous person. Because Isis was a goddess of magic who had fought Seth, she came to be regarded as a great benevolent goddess.

This religion became popular, and nowhere was it more popular than outside of Egypt. The Greeks and the Romans generally did not have gods who could promise eternal afterlife (such as Osiris) or benevolent magician deities (like Isis). Egyptian inspired cults filled a void in the popular needs of Greco-Roman society.

The Isis and Osiris cult swept the Hellenistic and Roman worlds and its cult began replacing the cults of the Olympians in popular loyalties. In Rome it was especially popular with women and people of foreign and lower birth - classes of people on the bottom of Roman society, in other words.

Like Christianity, it was a very popular religion with the urban proletariat, and if things had gone differently it might have replaced the Christian Holy Trinity with its own. As it is, some scholars think the relationship between Isis and Horus might have influenced early Christian thinking on the relationship between Mary and the Christ child.

The Ptolemaic Greeks and imperial Romans who came to conquer Egypt did not banish the native Egyptian religion (as has been said, Greeks and Romans often preferred Egyptian gods to their own).

But they did modify it to suit their needs. The cult of Isis and Osiris, for instance, started out as Egyptian but has many Greco-Roman influences. The Ptolemaic and Roman rulers tried to pass themselves off as Pharaohs. Despite this imperial meddling, Egyptian religion remained largely intact.

Later, when Christianity swept the Roman and then Byzantine worlds, there were still traces of native Egyptian culture and religion. Only the force of Islam totally eradicated a native faith and culture that had been practiced for thousands of years.

Interested in visiting Egypt? Be sure to check out our Egypt travel page!

Did you know...

During Roman rule, the Pharaohs were mere puppets of the Roman Empire. With the death of Cleopatra VII, the last of the Ptolemies to rule, and the defeat of the once-mighty Ptolemaic navy at Actium, in 31 BC Egypt became part of the Roman Empire under Augustus.

Did you know...

Military garrisons were stationed at Alexandria to keep the peace in Egypt, and no doubt to keep a close eye on the Alexandrian mob, which had not diminished over the years, but had stayed very much alive, and would continue to thrive under the Roman dominion.

Did you know...

Ma'at was the personification of the fundamental order of the universe, without which all of creation would perish. The primary duty of the pharaoh was to uphold this order by maintaining the law and administering justice.