Building the Pathways of Power

The Roman Empire, at its height, was a vast polity stretching across three continents - Europe, Asia, and Africa. Over the centuries, it developed highly sophisticated administrative, legal, and infrastructural systems to govern this enormous territory. One of the most remarkable and crucial institutions that bound this sprawling empire together was the Cursus Publicus ("the public way").

Although the term may suggest a postal system in the modern sense, it was in fact much more: the Cursus Publicus encompassed a network of roads, stations, stables, and personnel dedicated primarily to the swift movement of government officials, military troops, couriers, and crucial goods.

In this article, we will explore the origins of the Cursus Publicus, discuss its structure and functionality, and examine how it evolved and ultimately declined. By surveying its broad historical arc, we gain a window into the logistical brilliance of an empire that, for centuries, maintained unprecedented control over some of the most diverse and distant territories the world had ever seen.

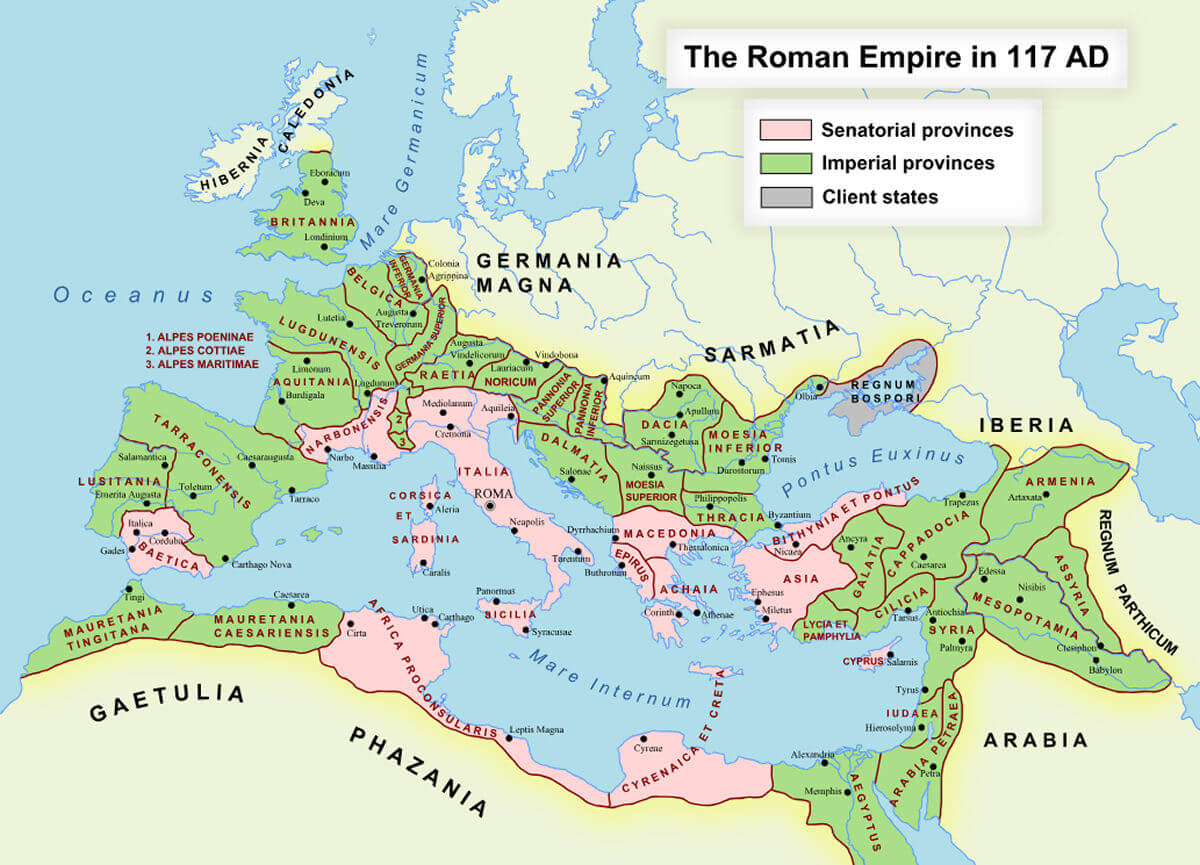

The provinces of the Roman Empire in 117 AD

Historical Origins

The Cursus Publicus was not built in a day, nor was it the product of one single emperor’s decree. Rather, it emerged gradually as the Roman state recognized the need for an organized system to facilitate rapid communication and facilitate travel for officials carrying out the empire’s business.

The seeds of this system can be found in the late Republic (1st century BC). Figures such as Julius Caesar, who famously sent dispatches back to Rome from Gaul, recognized the importance of swift communication in consolidating political power. With the rise of Augustus (r. 27 BC – 14 AD) and the establishment of the Principate, the bureaucratic machinery of the empire became more complex, and the Cursus Publicus began to assume a clearer shape.

Augustus not only reformed the army and administrative divisions but also made improvements to the road network. Indeed, the Romans had already become famous for their roads; straight, paved thoroughfares that connected distant provinces to Rome. These roads laid the essential foundation upon which the Cursus Publicus would thrive.

In the first few centuries of the empire, emperors such as Claudius, Vespasian, and Hadrian expanded and strengthened this system. The impetus was both administrative and military. Efficient communication was vital for maintaining order in regions such as Britannia, Dacia, and Syria, where newly conquered populations or restive frontiers demanded close oversight.

Over time, what began as an ad hoc arrangement evolved into a more structured network - complete with designated posts, lodging stations and specialized personnel - to support rapid travel and the exchange of information.

Administrative Structure

To comprehend how the Cursus Publicus worked, it is crucial to understand the administrative framework governing it. At the highest level, the emperor and his central administration oversaw the system. Since communication was vital to the flow of imperial directives, the emperor could not allow the courier service to be controlled by any local authority alone. Consequently, the institution fell under the aegis of centrally appointed officials who enforced the regulations and oversaw local operations.

Below the emperor and the imperial bureaucracy stood the provincial governors. Each province had its own administrative structure, led by a governor who represented the emperor’s interests and was responsible for upholding imperial law.

Governors depended heavily on the Cursus Publicus for official duties, such as coordinating troop deployments, collecting taxes, and managing civil affairs. They had the authority to issue travel warrants and manage the maintenance of stations within their jurisdiction, albeit under the watchful eye of the central government back in Rome.

The day-to-day operations of the Cursus Publicus were carried out by a cadre of lower-level administrators and support staff. These included station chiefs (mansionarii), who ran the mansiones (lodging stations), and those overseeing the mutationes (relay stations).

The station chiefs took care of everything from supervising stable-hands who looked after the horses to providing shelter, food, and fresh mounts for official travelers. Additionally, logistical personnel were responsible for procuring fodder, ensuring road maintenance, and handling expenses.

Two main branches of the Cursus Publicus are often distinguished in historical sources: the Cursus Velox (the “fast” service) and the Cursus Clabularis (the “wagon” service). The former was devoted to swift travel for critical messages and urgent state business, relying on horses or mules that could be exchanged frequently along the route. The latter, by contrast, was slower and focused on transporting heavier goods, typically using oxen-drawn wagons.

Key Components of the Cursus Publicus

Beyond its hierarchical administration, the Cursus Publicus was characterized by physical and operational elements that made it a remarkable feat of organization in the ancient world. Several of these are worth highlighting:

1. Roads: The physical backbone of the entire system was the Roman road network. Roads were expertly engineered to be long-lasting, with layers of stone and gravel providing a durable surface. Milestones, typically placed at intervals of one Roman mile (roughly 1,480 meters), gave distances in Roman numerals to important towns or the total distance to Rome. These roads minimized travel time, improved safety, and facilitated coherent route planning.

The Appian Way (Via Appia) Roman road

2. Stations: Along these main roads, as mentioned above, the Cursus Publicus established two types of primary stations:

- Mansiones: Larger lodging stations where travelers on official business could rest, eat, and, if needed, stay overnight. These were spaced about 25 to 30 kilometers apart, varying by the region’s terrain and the strategic importance of the route. Mansiones were often equipped with barracks, stables, food supplies and, occasionally, more comfortable accommodations for high-ranking officials.

- Mutationes: Smaller relay stations situated between mansiones. Typically spaced 8 to 10 kilometers from each other, these sites were used primarily for changing horses or mules, ensuring that couriers and officials could maintain a brisk pace without exhausting the animals.

3. Travel Passes: Known as diplomata or evectio, these documents confirmed an individual’s right to use the Cursus Publicus. Issued by the emperor, governors, or other authorized officials, the pass stipulated how many horses, mules, or wagons the holder was entitled to and for what distance. These passes acted as a form of currency within the system, ensuring that resources were not depleted by unauthorized travelers.

4. Animals and Equipment: Horses were the primary mode of transport for quick travel, particularly on the Cursus Velox, but mules, oxen, and donkeys were also used, particularly for hauling heavier loads. The Romans carefully bred animals suited to long-distance travel, and local authorities were typically required to provide fodder and stable areas.

Additionally, wagons and carriages varied in size depending on the type of load and the rank of the traveler; high-ranking officials often traveled in more comfortable carriages, while lower-level couriers made do with more modest vehicles.

5. Personnel: The Cursus Publicus relied on specialized workers - riders, grooms, blacksmiths, station managers and administrative clerks - to keep the system running smoothly. These individuals were often recruited locally, and their services were part of broader obligations (known as munera) required by the Roman state.

Roles in Imperial Administration

The Cursus Publicus was vital to a host of state functions, making it an essential tool in Rome’s strategy for governance. Several core roles stand out:

1. Military Coordination: Perhaps the most critical function was supporting the Roman military apparatus. Rapid communication of troop movements, frontier conditions, and strategic changes could mean the difference between losing or maintaining a province.

Generals and provincial governors alike depended on timely dispatches to orchestrate reinforcements, gather supplies, or issue new orders in response to local disturbances or barbarian incursions.

2. Tax and Revenue Management: Rome’s finances largely depended on taxation, tributes, and duties collected from diverse provinces. Efficient communication made it easier for central authorities to impose systematic assessments, track revenue, and address fiscal shortfalls.

Couriers also ferried official documents concerning tax rates, coinage and economic regulations back and forth between provincial authorities and the capital.

3. Civil Governance: Beyond the military and financial realms, the Cursus Publicus facilitated myriad civil administrative tasks. From coordinating census-taking to disseminating legal edicts and rescripts from the emperor, official messages were the connective tissue that allowed a coherent empire-wide government.

Judicial summons, diplomatic communiqués and intelligence reports also moved along the imperial roads, assisting governors and local magistrates in maintaining law and order.

4. Diplomacy: Contrary to the misconception that the Roman legions simply went in and claimed everything in their path, Rome often negotiated treaties or alliances with neighboring states, tribal leaders and foreign dignitaries.

Envoys traveling under official passes could rely on the Cursus Publicus for safe passage and stable accommodations. This allowed Rome not only to project power through swift communication, but also to manage external relations effectively.

5. Symbol of Imperial Authority: For Roman citizens, the visible presence of official couriers and traveling dignitaries underscored the reach and power of the emperor. The system’s existence reinforced the idea of a unified empire, where messages from distant frontiers could find their way to the capital in relatively short order. It was a logistical triumph that showcased Rome’s capacity for order and infrastructure on a scale few other ancient states could match.

Challenges and Reforms

Despite its remarkable capabilities, the Cursus Publicus faced recurring challenges. One of the most persistent problems was cost. Maintaining thousands of animals, stations, and personnel required significant resources.

While the empire demanded that local populations supply fodder, stables, and labor (as part of their taxation obligations), abuses of this system were common. Overburdened communities sometimes fell into hardship, prompting complaints about local elites using the service without proper authorization or burdening them with excessive demands.

Emperors and administrators frequently undertook reforms to manage these costs and reduce corruption. For instance, the issuance of travel passes came under tighter scrutiny: officials responsible for distributing them were urged to keep meticulous records to prevent fraudulent or excessive use.

Some emperors, such as Diocletian (r. 284–305 AD) and Constantine I (r. 306–337 AD), recognized that poorly regulated travel privileges could undermine both the financial base of provinces and the legitimacy of the entire system.

Diocletian reorganized the empire into smaller provinces governed by more directly accountable officials, which in turn affected how the Cursus Publicus was monitored. Constantine further regulated the Cursus Publicus, issuing specific restrictions on who could use it and for what purpose. These reforms aimed to streamline the service, ensuring it remained primarily for urgent state business rather than the personal convenience of the elite.

Yet, these measures did not always solve deeper structural issues. In the later empire, as frontiers became more insecure and local economies faltered, the burden on the Cursus Publicus to supply more troops, facilitate more urgent communications, and handle the logistical complexities of an empire under strain only increased.

Financial hardships made it more challenging to pay for upkeep, feed animals, and replace or repair station buildings. Furthermore, as certain territories were lost or became autonomous, the integrity of the road network suffered, weakening the efficacy of the system overall.

Regional and Geographical Variation

Although the Cursus Publicus was intended to be a uniform institution across the empire, regional variations inevitably emerged. Different terrains - whether the deserts of North Africa, the mountains of Asia Minor, or the dense forests of Germania - required adaptations in how stations were spaced, what animals were used, and how roads were constructed.

For instance, in Aegyptus (Egypt), a province of crucial importance due to its grain supply, the roads ran parallel to the Nile, and river transport often supplemented or replaced overland routes. The prevalence of camel caravans in certain parts of the East also influenced the ways goods and messages moved.

Along the Rhine and Danube frontiers, the threat of barbarian incursions and harsh winter conditions necessitated well-fortified routes, with some stations doubling as small military outposts.

This diversity across the empire made the Cursus Publicus an entity that, while bearing common organizational principles, also had to be malleable to local conditions.

Cultural and Social Impact

The Cursus Publicus was not just about efficiency and logistics; it also influenced the social fabric of the Roman Empire in subtle ways. For one thing, the stations and roads brought people from different provinces into contact. Couriers, officials, soldiers and merchants interacted as they traversed the empire, exchanging information, customs and goods.

While not everyone had access to the system, its presence facilitated a kind of connectedness that some historians argue contributed to an emerging sense of Roman identity, even if many in remote regions lived lives mostly untouched by direct imperial reach.

Moreover, the existence of such a system underscored the empire’s reliance on mobility. In an era with limited technology, harnessing the speed of horse relay stations was revolutionary. Diplomats, merchants, and elites from far-flung areas could actually hope to reach Rome in a matter of weeks rather than months. Military recruits transferred from one post to another gained exposure to new regions, forging personal links among different corners of the empire.

Yet, as touched upon earlier, this mobility came at a cost to local communities required to supply resources. The demands of hosting official travelers often led to tension. While the empire tried to regulate these burdens, the stationing requirements for animals, fodder, and lodging could strain local economies, especially in times of crisis or famine. It was not unusual to hear of peasants complaining about the demands placed upon them by unscrupulous station managers or traveling officials.

These difficulties highlight a recurring problem in ancient empires: the tension between the center’s needs for swift governance and the periphery’s capacity to sustain those needs.

Decline and Legacy

The decline of the Cursus Publicus is woven into the broader story of the Roman Empire’s transformation and eventual fragmentation in the West. From the 3rd to the 5th centuries AD, the empire faced mounting external pressure from various “barbarian” groups and internal upheavals - economic contractions, civil wars and administrative disarray - that collectively eroded imperial authority. As more resources were funneled into military defense, fewer were available for infrastructure and administrative upkeep.

Diocletian and Constantine’s reforms, while temporarily reenergizing certain aspects of administration, also introduced complexities. The empire was effectively split in two, with a Western and an Eastern half, each requiring its own bureaucratic apparatus. By the late 4th and 5th centuries AD, the Western empire, plagued by invasions (notably the Visigoths and Vandals), simply could not sustain many of its far-reaching institutions. The road network deteriorated, stations fell into disuse, and local leaders (both Roman and barbarian) replaced imperial officials.

Nonetheless, in the Eastern Roman Empire (later referred to as the Byzantine Empire), some aspects of the Cursus Publicus persisted in a modified form. The Byzantine emperors recognized the value of maintaining rapid communication across Asia Minor and the Near East, especially to coordinate military and administrative activity.

Although it never reclaimed the full scope and geographic reach that it had at Rome’s zenith, a semblance of the official post system lived on, influencing later medieval courier systems.

The legacy of the Cursus Publicus would not disappear entirely, even in Western Europe. The concept of an organized courier and transportation network for governmental use inspired subsequent states, including the Holy Roman Empire, and, much later, the modern postal services of Europe.

The very idea that a state could create a standardized infrastructure for official travel and communication has its roots in what the Romans established. Even the architecture of modern post offices and relay stations can be seen as distant echoes of Roman mansiones and mutationes.

The Cursus Publicus in Historiography

Modern historical scholarship on the Cursus Publicus draws on various sources, including legal texts (such as Diocletian’s 'Edict on Maximum Prices'), administrative codes, the writings of Roman historians and letter-writers like Ammianus Marcellinus, and physical evidence from excavations along Roman roads.

These diverse materials provide glimpses into how the system functioned in everyday life, although inevitable gaps in the record leave historians piecing together an incomplete puzzle.

Some debates revolve around the extent to which the Cursus Publicus was accessible and to whom. While it was designed for official use, the question remains: did it sometimes, in practice, serve the private interests of the higher social classes, particularly those of well-connected elites or merchants who could bribe officials?

Additionally, scholars continue to explore how effectively the system coped with severe crises, such as plagues and heavy warfare. During periods of relative stability, the Cursus Publicus seems to have been a smooth-running machine; in times of chaos, it likely fractured more quickly than the central authorities cared to admit.

Another point of historiographical interest concerns the Cursus Publicus' relationship with the broader Roman economy. While primarily an administrative institution, it indirectly supported trade by improving the safety and reliability of major roads. Traveling merchants, though not officially granted the same privileges, could benefit from the infrastructural solidity and relative security that well-maintained roads and stations afforded.

In that sense, the system may have had positive spillover effects on economic life, contributing to the prosperity observed in many regions during Rome’s imperial heyday.

In Conclusion: Rome’s Mastery of Communication and Logistics

The ancient Roman Cursus Publicus stands as an extraordinary testament to the administrative ingenuity of one of history’s greatest empires. At its core, it was a state-run courier and travel service, replete with roads, stations, animals, and personnel stretching from the British Isles to the deserts of Mesopotamia. In a world without modern communication technologies, this system bridged vast distances, facilitating the swift movement of officials, soldiers, couriers, and vital correspondence.

Its success was rooted in Rome’s broader commitment to infrastructure; the famous roads, aqueducts and public works that came to symbolize the empire’s power and order. Indeed, the Cursus Publicus depended on this network of meticulously engineered routes and cleverly spaced stations, ensuring that messages and directives from the emperor could travel hundreds of miles in surprisingly short periods.

Yet, the Cursus Publicus was far from perfect. Its operational costs, the burden on local communities, occasional corruption, and the stress of constant military campaigns all took their toll. The reforms instituted by emperors like Diocletian and Constantine kept the system alive for a time, but they could not halt the deeper structural shifts that would fracture the empire.

As the Western Empire crumbled under the weight of invasions, economic decline and administrative disarray, many of the roads and stations fell into disrepair. Only in the East, under Byzantine rule, did a streamlined adaptation persist, bridging the legacy of Rome with the needs of a changing political landscape.

Ultimately, the Cursus Publicus offers modern observers not just a lesson in logistics but also a glimpse into the complex dynamics of empire. By controlling and regulating travel and communications, Rome secured a measure of cohesion and surveillance over its territories unrivaled in the ancient world. This system served as a linchpin of governance, military control and symbolic imperial authority.

Even after the fall of Rome in the West, the fundamental concept - a state-managed network ensuring rapid communication - would resonate through medieval Europe and beyond, informing the later development of postal systems.

In hindsight, few institutions better exemplify Roman organizational prowess than the Cursus Publicus. It was, in many respects, a backbone of the empire’s day-to-day functioning, weaving together an immense territory into a single administrative and cultural tapestry. The success and longevity of this courier service illuminate why Roman roads were so crucial to the imperial project.

Today, as we examine the remnants of mansiones and mutationes scattered across Europe, the Near East and North Africa, we recall an era when the fate of legions, the decisions of emperors, and the fortunes of provinces all depended on the well-trodden paths of the Cursus Publicus, the “public course” that once carried the voice and will of Rome itself.

Did you know...

During the Roman Republic, tax revenue collection was left to "publicani", so called because they won by highest bid the contract to collect the revenues. It was the governor's responsibility to keep the publicani within the bounds of the "lex provinciae", so that they did not exploit the helpless provincials too mercilessly.