Romulus Augustulus (462 - 511 AD)

Emperor: 475 - 476 AD

Few figures in Roman history are as emblematic of a grand empire’s final twilight as Romulus Augustulus, traditionally regarded as the last emperor of the Western Roman Empire. While his reign was brief - lasting only from October 475 AD to September 476 AD - Romulus has loomed large in the historical imagination due to the significance of his deposition.

His removal from power is often cited as a watershed moment that signaled the “fall” of the Western Roman Empire, an idea that has shaped countless historical narratives. Yet behind this familiar narrative lies a more nuanced story: Romulus Augustulus was, in reality, a child-ruler lacking true imperial power, thrust into a position he likely neither sought nor fully understood.

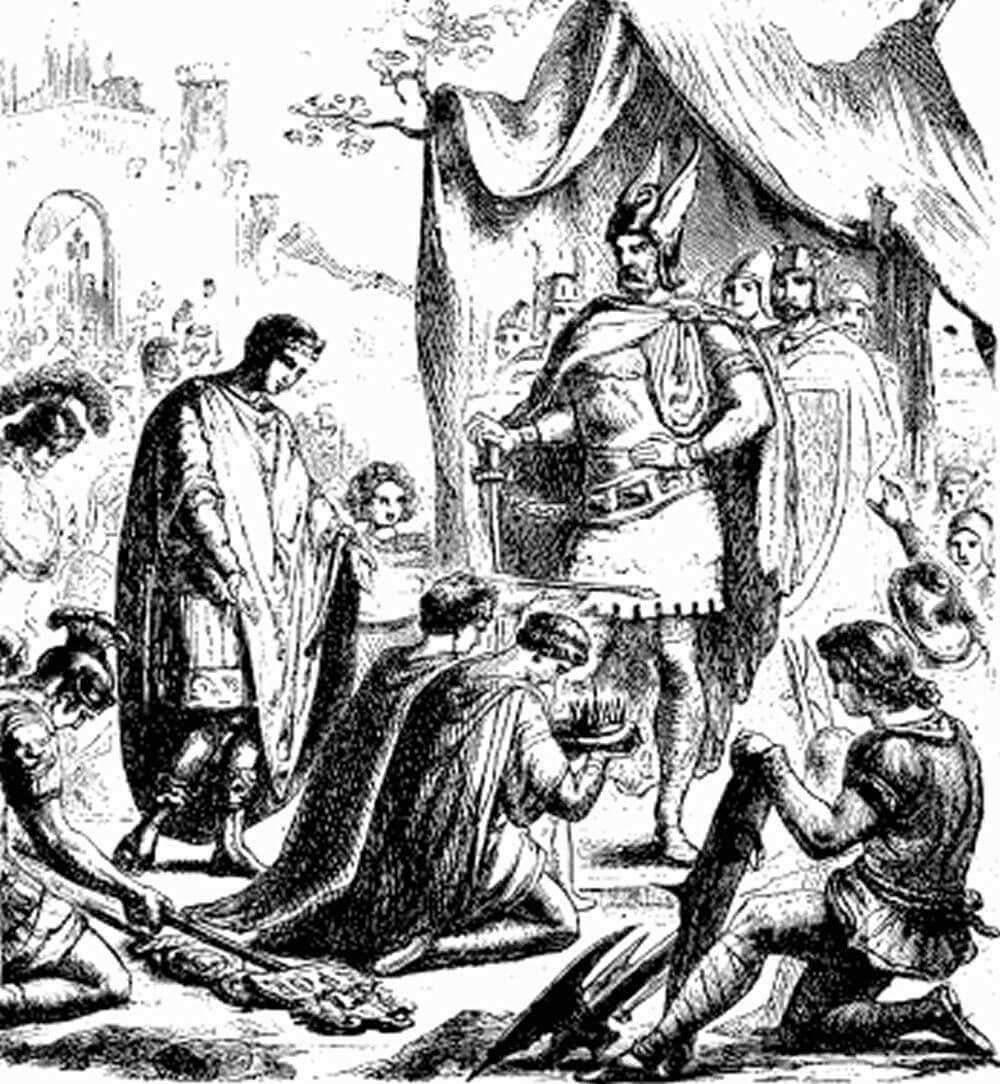

Romulus Augustulus surrendering his crown in front of Odoacer by Charlotte Mary Yonge (1880)

The Late Western Empire: Historical Context

By the mid-fifth century AD, the Western Roman Empire was in a precarious position. A series of internal struggles, economic crises, and external pressures had eroded the might of what was once the most formidable power in the Mediterranean.

To the north, Germanic tribes - such as the Goths, Vandals and Suebi - had been encroaching upon Roman lands for decades, pushing the frontiers ever southward and westward. To the east, the Eastern Roman Empire (with Constantinople as its capital) endured more effectively, partly because it was wealthier and more urbanized, and partly because it had successfully cultivated complex diplomatic relationships with neighboring peoples.

The Western Empire, based in the city of Ravenna since Honorius moved it in the early fifth century AD, suffered constant upheavals as generals and regional warlords jockeyed for supremacy. In Rome itself, the ancient Senate had lost much of its former influence, though it still held symbolic power. Imperial authority in the West rested on precarious alliances with foederati; barbarian contingents serving under Roman command in exchange for land and privileges.

The emperors in Ravenna became increasingly reliant on these federate troops to maintain control over rebellious provinces. One such general was Flavius Orestes, a figure whose ambition and maneuvering would propel his son, Romulus, to the throne for a fleeting moment in history.

Amid this tumult, the line between a legitimate emperor and a usurper grew hazy. Many leaders ruled briefly, recognized by only a portion of the empire or declared legitimate by the Eastern court while lacking any real authority in the West. In this environment, child-emperors, puppet rulers and short-lived reigns were not uncommon.

When Romulus Augustulus emerged in 475 AD, he became a symbol of a once-glorious empire’s final grasp at traditional continuity - a hope that would soon be dashed by political machinations and the unstoppable momentum of change.

Childhood and Background of Romulus Augustulus

The exact birthdate of Romulus Augustulus is not known with certainty, but historians generally place it around 462 AD. His father, Flavius Orestes, was a Roman citizen of Pannonian origin who had risen to prominence as a trusted official under Western Emperor Julius Nepos.

Orestes had previously served in the court of Attila the Hun during the early 450s AD, hinting at a complex political background and demonstrating the fluidity of loyalties in that era.

Romulus’ mother’s identity is less clear, though some sources suggest she may have been related to prominent families with Germanic ancestry, reflecting the increasingly multicultural makeup of the late empire.

Named after two legendary Roman figures - Romulus, the mythical founder of Rome, and Augustus, the first Roman emperor - Romulus Augustulus bore a name steeped in Rome’s grandiose past. The nickname “Augustulus,” meaning “little Augustus,” may have been either a term of affection, or a sarcastic commentary on his youth and the diminished state of the empire he was meant to rule.

Given that he was probably only in his early teens when he ascended the throne, Romulus was a minor with no independent authority. The Western Roman Empire had seen a series of puppet emperors in the decades before him, but none so young and vulnerable to the machinations of ambitious generals.

Despite the significance of his name, the boy likely had little understanding of the political winds swirling around him. His upbringing, like that of many aristocratic children of the era, would have included basic literacy in Latin and perhaps Greek, some knowledge of Roman law, and Christian religious instruction. Still, any potential for a rigorous imperial education was cut short by the tumult in which he would find himself.

Orestes’ Ambitions and the Road to Power

Flavius Orestes’ path to power began in earnest when he served as a high-ranking military officer under Emperor Julius Nepos. In 475 AD, however, Orestes launched a revolt against his benefactor. Nepos, taken by surprise, fled to Dalmatia (in modern-day Croatia), leaving the imperial seat at Ravenna vacant.

Rather than claiming the throne himself - an act that might have drawn the ire of competing generals and the Eastern Roman Emperor - Orestes placed his young son, Romulus, on the throne as a figurehead.

Though it is tempting to view Romulus as little more than a pawn in his father’s ambitions, this scenario was relatively standard in the disordered political context of the fifth-century Western Empire.

Military strongmen had come to dominate the political sphere, leveraging puppet emperors who bore the nominal legitimacy of Rome’s August tradition, while the real power resided in the hands of generals and regional warlords. By installing his son, Orestes could govern behind the scenes, use the imperial image for propaganda and, if necessary, sacrifice the youthful emperor if political tides turned.

The Eastern Roman Empire, ruled at that time by Emperor Zeno (r. 474–475 and 476–491 AD), did not officially recognize Romulus as the legitimate Western Emperor (Zeno continued to acknowledge Julius Nepos as the rightful ruler in the West). Nonetheless, Orestes and his son controlled the machinery of state in Ravenna, and for all practical purposes, Romulus Augustulus was the emperor on the ground. Coins were minted bearing his name, and official documents presumably recognized his status.

Yet the façade of legitimacy could only go so far when political power was so precariously balanced on the tip of a sword.

A gold solidus coin featuring Romulus Augustulus

The Short Reign of Romulus Augustulus

Romulus Augustulus’ accession to the throne on 31 October 475 AD quickly became overshadowed by deeper social and military forces at work in the Western Empire. Within months of his proclamation, the new puppet emperor faced threats that neither he nor his father could easily quell.

Perhaps the most pressing challenge came from the federate troops stationed in Italy, many of whom were of Germanic origin and chafed under Orestes’ authority. These troops demanded land settlements in Italy; compensation for their service in defense of a declining empire that struggled to meet its financial obligations.

When Orestes refused to grant these lands, the federate forces found a leader in Odoacer, a chieftain of likely Scirian background, who commanded significant loyalty among Germanic soldiers. Initially serving under the Roman banner, these soldiers now saw no reason to remain loyal to a Roman general who denied them the tangible rewards they sought. Rumblings of discontent began to shake the foundations of Romulus’ rule, even as the boy-emperor may have been scarcely aware of the imminent danger.

Beyond the immediate threat of rebellion, Romulus Augustulus also faced the more general crisis of a collapsing Western Roman administrative framework. Provinces such as Gaul (modern France) and Hispania (modern Spain) had already been carved up by various Germanic rulers, and Rome’s control over distant regions had dwindled to a shadow of its former strength.

Any symbolic authority Romulus might have enjoyed as emperor was undercut by the reality that his father’s regime had few allies, and even fewer resources, to manage an empire in freefall.

Within the internal politics of Italy itself, aristocrats and Roman elites were divided. While some supported Orestes’ claim because it promised local stability, others saw better opportunities in forging alliances with powerful Germanic leaders. All of these factors converged rapidly, overshadowing the ephemeral reign of the child-emperor, who seemed ill-fated from the very start.

The Deposition by Odoacer

By August 476 AD, the discontented federate troops under Odoacer decided to take matters into their own hands. Mounting a rebellion, they quickly overran Orestes’ forces. Orestes himself was captured and executed, while his brother Paulus also met a similar fate. With the emperor’s father removed, Odoacer entered Ravenna, the seat of Western imperial power. The city surrendered without significant resistance, and Romulus Augustulus found himself at the mercy of the victorious Germanic warlord.

The fate of deposed emperors could be grim; many were assassinated, exiled, or forced to end their own lives. Yet in a display of magnanimity - or political calculation - Odoacer spared the young boy. Perhaps recognizing that Romulus Augustulus posed no real threat, Odoacer chose to dethrone rather than kill him.

In a symbolic gesture, Odoacer also took from Romulus the imperial regalia - such as the purple robes and other insignia - and dispatched them to the Eastern Emperor Zeno. This act carried a potent political message: there was no longer a need for a separate Western Emperor, and the line of Western Augusti would effectively end with this boy.

Traditionally, historians pinpoint 4 September 476 AD as the official date of Romulus’ removal from power, though the precise dating varies in different sources. This event - though it was likely seen at the time as just another palace coup in a series of upheavals - became enshrined in history as the “fall” of the Western Roman Empire.

Scholarly debate continues as to whether 476 AD truly marked the empire’s collapse; after all, many Roman institutions continued under Odoacer and, later, under Ostrogothic rule in Italy. Nonetheless, the fact that Romulus bore the imperial name and lost his throne to a Germanic king with no interest in installing a new Western Emperor gave the event its enduring significance.

After the Fall: The Exiled Emperor

Exile was a common solution for dealing with dethroned child emperors, especially if they posed little political threat. According to most accounts, Odoacer sent Romulus Augustulus to live in relative comfort at the Castellum Lucullanum, a fortress in Campania near Naples. This estate, which had belonged to the imperial treasury, was transformed into a sort of genteel prison where Romulus could live out his days without interfering in political affairs.

Little is known of Romulus’ life in exile. Some accounts suggest that Odoacer granted him an annual pension, further indicating a degree of kindness (or at least, disinterest) from the new ruler. Other accounts, including that of the historian Jordanes, claimed that Romulus survived long into adulthood, though the historical record is murky. One story even claims that he later retired or died in anonymity, possibly as a monk, but these stories are generally considered speculative.

What is evident is that, despite being an emperor in name, Romulus Augustulus had almost no real role in shaping the political or military direction of the Western Empire. By the time he was exiled, the machinery of Western Roman governance was effectively dismantled, taken over first by Odoacer and later by Theodoric the Great, the Ostrogothic king who conquered Italy at the end of the 5th century AD.

Rome itself had, by then, become more of a relic of an imperial past; the city that once presided over the entire Mediterranean was subject to frequent sackings and overshadowed by the new power centers in the region.

A Symbolic End: Why 476 AD Matters

The deposition of Romulus Augustulus in 476 AD has long been taught in Western historiography as a major dividing line between antiquity and the Middle Ages. This symbolic date resonates because of the potent images it conjures: a child ruler with a storied name, the transition of power to a Germanic king, and the symbolic act of returning the imperial regalia to the Eastern Emperor.

Yet historians have long recognized that this “fall” was not as abrupt or definitive as many popular narratives suggest. Even by the time Romulus came to power, large swaths of the Western Empire were already under Germanic rule. The administrative structures of Rome had already been changing and evolving for centuries beforehand.

Still, 476 AD does serve as a powerful historical marker. First, it underscores how political and military authority in the West had diffused to the point of irrelevance for the Roman imperial office. Second, it neatly marks the moment after which no new Western Emperor was installed - a recognition that the idea of a separate Western imperial line had become unnecessary. The Eastern Emperor, from then on, viewed himself as the sole Roman Emperor, at least in principle. Third, in later centuries, scholars and chroniclers seeking a clear-cut “fall” date latched onto Romulus Augustulus as a symbol: the last vestige of Roman authority undone by a barbarian warlord.

In reality, the cultural and societal transformations that led to the medieval world were more gradual and complex. The Western Roman Empire did not collapse uniformly; the process had been a centuries-long decline, punctuated by occasional resurgences (like Majorian’s campaign in the mid-fifth century AD).

But just as certain battles and dates - like the Battle of Actium in 31 BC, or the Sack of Rome in 410 AD - are remembered for their iconic meaning, the “fall” of Romulus Augustulus in 476 AD remains one of the most enduring markers of historical change.

The Forgotten Emperor: Life, Legacy, and Mystery

After his exile, Romulus Augustulus largely vanished from the historical record. Few contemporary sources offer insight into his later life, a stark contrast to the meticulously documented reigns of earlier Roman emperors like Trajan or Marcus Aurelius for example.

This silence highlights the marginal importance of a dethroned adolescent emperor in a changing political landscape. Without the resources or alliances to attempt a comeback, and without a strong faction insisting on his restoration, Romulus Augustulus simply faded into obscurity.

Multiple theories have been posited as to what became of him. A letter written by the Eastern Roman statesman, Cassiodorus, in the early sixth century AD references a figure named “Romulus” living on an estate in the region of Campania, suggesting that the exiled emperor might have survived into adulthood, and perhaps even witnessed the early phases of Ostrogothic rule in Italy.

As mentioned, other writers hint that he eventually became a monk, presumably spending his final years in religious devotion. However, none of these accounts are by any means definitive.

Romulus Augustulus’ anonymity stands in stark contrast to the powerful legacy of his name. Earlier Romulus was credited in Roman mythology with the founding of the city; Augustus established the Principate, ushering in two centuries of imperial splendor. Romulus Augustulus, by the end of the fifth century AD, symbolized the Roman Empire's collapse in the West.

The arc of Roman history seems encapsulated in the parallel between the first Romulus, the founder, and the last Romulus, the forlorn teenager stripped of his title. Over time, historians and artists would revisit Romulus Augustulus, sometimes romanticizing his misfortune, sometimes using him to evoke a dramatic sense of an ending.

Historiographical Debates and Interpretations

The “fall of Rome” has been debated by historians for centuries, from Edward Gibbon’s monumental work, The History of the Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire, published in the late eighteenth century, to contemporary scholarship that questions the very notion of a “fall.” Romulus Augustulus inevitably appears in these discussions as the figurehead of the Western Empire’s final gasp, though interpretations differ widely.

These historiographical debates highlight the importance of interrogating the idea of “ends” in history. While the political reality of a Western Emperor evaporated in 476 AD, the underlying fabric of Roman life did not vanish overnight.

The Roman Senate persisted, at least symbolically, under barbarian rule. Roman law codes, such as the Theodosian Code, continued to influence legislation throughout post-Roman kingdoms. Latin remained a lingua franca, evolving into the Romance languages over centuries. Despite his ephemeral rule, Romulus Augustulus plays a large role in how we conceptualize one of history’s most widely discussed transformations.

Concluding Thoughts: The Last Emperor, the Uncertain Legacy

Romulus Augustulus’ story encapsulates the paradox of the Western Roman Empire’s final decades: a facade of imperial continuity overshadowed by the rise of Germanic military power, the fragmentation of the Roman world, and the unstoppable tide of transformation that would define the early medieval period.

Placed on the throne by his ambitious father, he served as a youthful proxy for imperial authority in an era that no longer recognized the power or prestige of Rome’s ancient lineage. Within a year of his elevation, Odoacer’s coup swept him off the stage of history, relegating him to a lonely exile.

Yet although his direct influence on historical events was minimal, Romulus Augustulus endures as a poignant symbol. His deposition effectively ended the line of Western Roman Emperors, an institution that had stretched back (in some form) to Augustus Caesar himself, five centuries earlier.

The memory of the boy-emperor’s downfall continues to resonate, not because his personal rule marked a dramatic turning point, but because historians and chroniclers have latched onto the drama of a child losing an empire - a narrative that resonates with themes of lost glory, decline, and the inevitability of change.

In many ways, Romulus Augustulus was a passive actor in a much larger historical process. The Western Roman Empire did not so much collapse at a single moment, rather, it gradually transformed and disintegrated under the pressure of long-term social, military, and economic factors. By the time Romulus donned the imperial purple, there was little left to save. His dethronement served as a tidy symbol for a transition that had been underway for decades, if not centuries.

Whether we view him as the last Western Emperor or simply a footnote to Julius Nepos’ contested claim, Romulus Augustulus offers insight into the final phase of Roman imperial rule in the West. Despite his personal obscurity, he stands as a reminder that historical “endings” are rarely as neat or as absolute as the stories we tell.

Still, few figures can match the dramatic irony of a boy named for Rome’s founder, crowned in imitation of its first emperor, and dethroned as the Western Empire breathed its last. The child who once wore the imperial regalia embodies both the grandeur of Rome’s past and the fragility of its final days—a lasting testament to how empires rise and fall, often in ways that defy simple explanation.