Tin and the Phoenicians

Some of the earliest references to tin come from Phoenician traders dating to 1500 BC. Phoenician colonies (later Carthaginian) that developed in what is now southern Spain traded avidly with local residents. A colony, Gadir (Cadiz) founded (circa 800 - 600 BC) near the Guadalquivir River was a prime destination for locally mined silver and tin.

Additional sources have been vaguely referenced only as the Tin Islands (Cassiterides), which the Phoenicians kept as a closely guarded secret. Of course, we now know that these islands represent the farthest reach of the ancient world, the British Isles. One of the world's first and foremost historians, Herodotus, referenced the Cassiterides as early as the 5th century BC, but had little to no knowledge of where they actually were.

Tin and the Celts

Between the time of Phoenician Mediterranean dominance and the rise of the Romans, the Gallic Celts established themselves as masters of metalworking. The Celts were among the first to develop bronze working, using copper and tin to form a stronger alloy metal, and their craftsmanship was second to none. Even well into the Roman period, some of the most finely crafted metal works came from the Celts, and the tin trade was certainly robust.

The Greeks used Celtic and Germanic traders to import tin across land routes. They traded heavily with these northern tribes, importing such items as metals, glass, amber and various grains. Tin, however, with its importance to the bronze industry, was among the most profitable of commodities.

There is evidence that the Carthaginian admiral, Himilco, found and developed Phoenician tin mines in northwestern Europe in the 6th century BC. First establishing the mine of Morbihan and exhausting its sources on the western Gallic tip of Amorica, he then apparently was among the first southern Europeans to establish a foothold in Britain.

Mines were established in Cornwall, but it seems that the cost or potential danger of these expeditions led to its abandonment to local Celts. After this expedition, the Celts controlled the British tin industry for another five years, leaving the Carthaginians to their Spanish colony of Gadir.

Tin and Other Minerals in Britain were Likely a Significant Factor for the Romans Invading

By the invasions of Caesar in the mid-first century BC, the British source of tin was certainly known to the Romans. His invasions, though with several other motives, may have been partially inspired by the thought of controlling the valuable mines of Britannia.

While securing trading partners among local tribes, conquest and Roman control of the British mining industry would take another century, coming with the invasion of Claudius.

Why Was Tin So Important?

Weapons

Perhaps the most important use of tin in the ancient world was the production of the bronze alloy. While copper was the primary ingredient, tin was required at a proportion of about 10%. Bronze has been found in ancient art dating as far back as 3000 BC in Egypt, Mesopotamia and Persia. Whilst these early bronze sources obviously used tin, the sources are relatively unknown.

Interestingly, the use of iron didn't necessarily replace bronze. Despite the advancement of the 'Iron Age' for tools and other metal works, bronze was a far sturdier and more effective metal for use in weaponry. Bronze, and therefore, the use of tin in weaponry wasn't fully replaced until the introduction of steel (though somewhat unknowingly) during the Roman age.

Other Important Uses

The Phoenicians used tin in the production of its famous purple dye from Tyre. Tin was found to be the most effective vessel to store the combined liquids of the dye while they evaporated.

Tin was also an important product for use in solders. Mixing tin with lead to make it melt easier, solders were used in all sorts of crafts including jewelry, metal containers and tools. The use of tin solders in lead pipe plumbing made effective sealants possible to carry water uninterrupted throughout the Roman Empire.

Did you know...

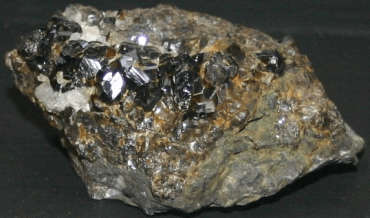

Cassiterite is the ore from which tin is extracted. The word comes from the ancient Greek 'Kassiteros', meaning tin.