Copper in Ancient Times

Archaeological evidence indicates that copper was used as far back as 10,000 years ago in western Asia. During the prehistoric Chalcolithic Period (Homer, following the Greek practice of around 1000 BC, called the metal Chalkos, which is why the Copper Age is also known as the Chalcolithic Era), societies discovered how to extract and use copper to produce ornaments and implements.

As early as the 3rd - 4th Millennium BC, copper was actively extracted from Spain's Huelva region. Around the year 2500 BC, the discovery of useful properties of copper-tin alloys led to the Bronze Age.

Copper Was Used by the Ancient Egyptians

It has been documented that Israel's Timna Valley provided copper for the Pharaohs. Papyrus records from ancient Egypt reveal that copper was used to treat infections and sterilize water. The island of Cyprus is known to have supplied much of the copper needed for the empires of ancient Phoenicia, Greece, and Rome.

In their hieroglyphics (picture writing), the ancient Egyptians used the Ankh sign to represent copper. The Ankh was also the symbol of eternal life, which is appropriate for copper since it has been used continuously by people for 10,000 years.

Copper Has Many Uses, Including Coins

While the Greeks during Aristotle's era were familiar with brass, it was not until Augustus' Imperial Rome that brass became abundantly used. Replaced by iron for weapons and tools, copper and bronze became metals used in architecture, art, and certain specialized uses such as copper pots. The alloy brass, in which copper is mixed with zinc, was discovered sometime before 600 BC.

The state of Lydia, south of Troy in western Turkey, invented the idea of coins as a medium of exchange. Coins were small and portable, had a set value, and were more convenient for trade than the bulky system of barter. Gold, silver, copper, and bronze were used for coins, a use that continues today in our penny. Greek coins with the head of an owl on the back, known as "Owl Coins", were the most important medium of exchange in the 5th century BC. Thus, the idea of money was born.

The Etruscans reached the glorious days of their civilization about 800 BC, before the rise of Rome. They were descendents of immigrants from Lydia. In the mountains of the modern Italian province of Tuscany, the ancient Etruscans found copper and tin ores. Iron ore was conveniently near on the Island of Elba. While they created superb iron weapons, they produced magnificent statues in bronze.

Joining the Phoenicians in seafaring trade, the Etruscans were rivals of Greek traders around the Mediterranean Sea. Caught between Gaulic invasions from the north and the rising Roman city-state to the south, the last Etruscan city yielded to Rome in 396 BC.

Recycling Copper in Ancient Rome

Pliny the Elder, the famous Roman historian, wrote in the first century AD about the reuse of scrap copper in Roman foundries. He noted that the metals were recast as armor, weapons or articles for personal use, such as bronze mirrors.

The melting and recasting foundries which he alluded to were located at the Italian port city of Brindisi. This city, situated on the Adriatic coast, was the terminus of the great Appian Way, the Roman road constructed to facilitate trade and military access throughout the Italian part of the Roman Empire. Thus, the city was the gateway for Roman penetration to the eastern parts of her empire.

Expansion of the Empire Brought Much-Needed Resources

In order to support its growing empire, Rome explored extensively throughout the Mediterranean region in search of mineral wealth. During this time, the Romans also managed to acquire a vast amount of mineral wealth from the Phoenician colony of Carthage, which they had destroyed. This wealth included the great metal mines located in Spain.

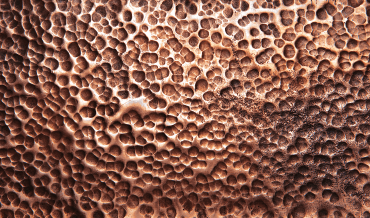

In particular, a huge copper deposit was discovered in the southwest corner of Spain, and the copper and iron present on the surface of the Earth at this deposit caused a nearby river to turn red. This river was thus named Rio Tinto, and the entire mining district was also named after it.

Originally, the deposit consisted of a reddish mountain, which contained not only copper but also iron, silver, and gold. However, after three thousand years of mining, the mountain has been completely depleted, leaving behind a crater where it once stood.

The crater is over 800 feet deep and over three-quarters of a mile wide. In the walls, one can see remnants of Roman tunnels and shafts, and water wheels with bronze axles that were used to lift water out of the ancient tunnels can still be found. Slaves ran the water wheels by walking on treadmills.

Mining techniques changed very little over the years. Besides using fires to crack rock, quicklime was stuffed in cracks then wetted with water. As it became wet, the quicklime expanded, breaking off chunks of rock as it did so.

To allow miners to carry ore to the surface, spiral stairways were cut in the rock around the sides of shafts. Where the space was too cramped for stairs, notched poles were used as ladders. Up to 200 hundred pounds were carried by each worker in leather buckets on their backs.

Unfortunately, the deep mine workings tended to fill with water, despite the water wheels. A drainage tunnel over a mile long and reaching a thousand feet deep was dug to join up with the mines.

Slaves, Workers and Labor Laws

In the early days of the Roman Empire, conquests of new lands were being made at a great rate. As a result, many prisoners of war were carried to Spain as slaves. Because slaves were plentiful, conditions were horrible for the workers in the mines.

Later on in the Roman Imperial period, when new slaves were less easy to obtain, slaves became more valuable. Roman labor laws were passed that mandated working conditions for the slaves in the mines. Tunnels and shafts had to be supported adequately with timbers, in order to prevent collapse. Miners were entitled to sleeping and bathing accommodations, food, and specific hours of work.

These labor laws were more humane than many miners faced in the early 20th century!

The area of Rio Tinto is still being mined today, although now the miners are working in open pits, rather than the tunnels of the ancient Romans. Millions of tons of black slag remain from Roman smelting operations, which contains small amounts of gold and silver, as well as copper, showing that the Romans were interested in these precious metals.

Miners today are mining brassy yellow copper "sulfide" minerals such as chalcopyrite. The sulfides were more difficult to smelt than the green and blue copper "oxide" minerals used by the Sumerians. The Romans were fortunate that the oxide ore was closer to the surface, and that there was a great deal of it.

Sulphite Minerals

Despite the difficulties involved, the Romans did manage to find a way to extract copper from the sulfide ores, although the process was slow and likely produced only a small amount of copper.

They accomplished this by collecting water that had seeped through the mines. The copper present in the ores caused the water to turn blue, while the sulfur in the minerals was converted into a combination of oxygen and sulfur known as "sulfate" (when sulfate is present in water, it creates sulfuric acid).

The blue water that resulted from this process was referred to as chalcanthus by the Romans. When this blue water was dried out, it resulted in a copper sulfate mineral of the same light blue color, which was called chalcanthite.

The Roman Empire's expansion and wealth depended on mines outside of the boundaries of the original Roman city state. Exploration for new mineral wealth was often the motive for Roman military expansion. Julius Caesar, for example, sought to increase his personal fortune by controlling the tin deposits of Cornwall, when he invaded Britain.

In order to smelt "sulfide" minerals, which are minerals made up of copper, iron, lead and zinc chemically bound to sulfur, they must first be heated and "oxidized". However, by the time of the fall of Rome, the more easily smelted ores had already been exhausted.

During the Middle Ages, the Moors inhabited southern Spain and made use of copper for both cooking utensils and ornaments. In order to continue mining the still vast sulfide ore deposits of Rio Tinto, they developed a new process.

This process involved collecting the ore, breaking it into pieces, and piling it into heaps. Water was then allowed to seep down through the heaps, which was subsequently collected. This technique is referred to as "heap leach".

As a result of this process, the resulting solution contained copper in the form of copper sulfate, and there was far more copper in the water than in the mine water collected by the Romans. Iron was then placed into the water containing copper sulfate, which caused a reaction to occur. During this reaction, the iron dissolved into the water, while copper precipitated where the iron had been.

Did you know...

Copper was the first metal used by man in any quantity. The earliest workers in copper soon found that it could be easily hammered into sheets, and the sheets in turn worked into shapes which became more complex as their skill increased.