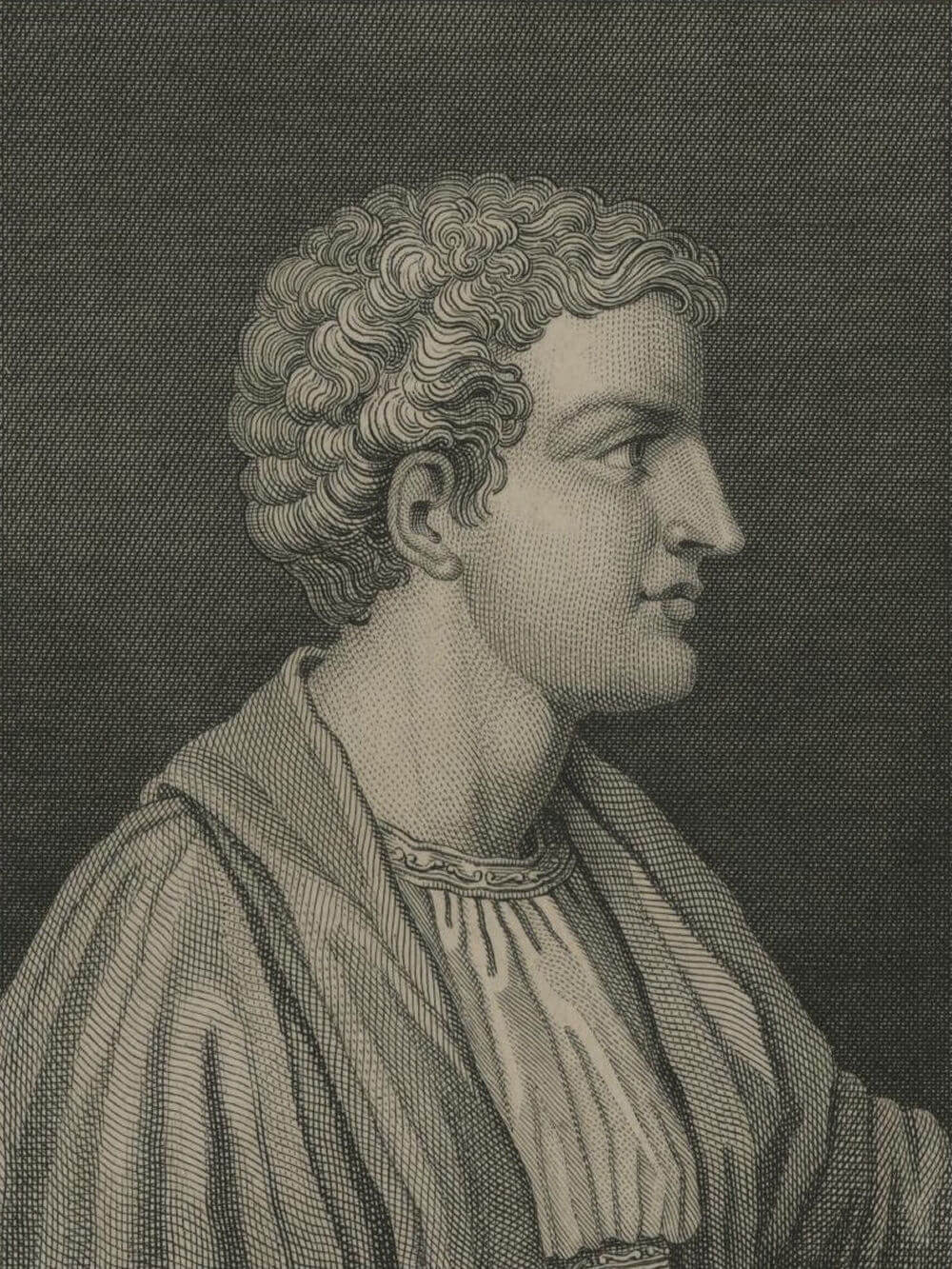

Quintus Horatius Flaccus (65 - 8 BC)

Quintus Horatius Flaccus (65 BC – 8 BC), universally known in English simply as Horace, stands among the most celebrated poets of ancient Rome. His works, particularly the Odes and Satires, have resonated for more than two millennia, influencing literary traditions well into modern times.

Born in the generation after the civil war between Julius Caesar and Pompey, and living through the establishment of the Principate under Augustus, Horace's life and writing reflect a period of extraordinary political and cultural transformation.

Horace in a late 18th to early 19th century engraving

Historical Context and Early Life

Horace was born on 8 December 65 BC, in the town of Venusia (modern-day Venosa) in the southern region of Italy known as Apulia. At the time of Horace's birth, the Roman Republic was at the tail end of its existence. It was caught in the throes of political turmoil, marked by power struggles between influential generals and statesmen.

Horace's father was a freedman, likely once enslaved but emancipated before Horace's birth. This fatherly figure, despite modest financial means, invested heavily in his son's education. By his own admission, Horace regarded his father as a man of exceptional character: forward-thinking, diligent, and determined to provide Horace with the best possible intellectual and moral foundations.

Eager to see his son succeed, Horace's father moved with him to Rome and paid for tutors often reserved for children of the Roman elite. This education cultivated the boy's burgeoning talents, exposing him to the finest Latin and Greek texts of the day. Indeed, Rome at the time was abuzz with cultural exchange; Greek ideas and styles flowed into Roman society, shaping elite tastes in literature, philosophy, and art.

Horace's early schooling in such an environment laid the groundwork for his lifelong engagement with Greek poetic traditions, notably the lyric verse of Alcaeus and Sappho, as well as the philosophical musings of Epicurus.

Upon completing his initial studies in Rome, Horace traveled to Athens for advanced philosophical training, in what was then one of the world's foremost centers of learning. Athens in the mid-first century BC was still a hotbed of intellectualism. Though politically subordinate to Rome, Greek culture continued to exercise a strong influence on Roman youth pursuing higher education.

Horace immersed himself in rhetoric, philosophy, and the Greek literary tradition, further refining the linguistic and conceptual tools he would later employ in his poetry.

Political Turmoil and the Return to Rome

The assassination of Julius Caesar in 44 BC launched the Roman world into renewed civil conflict. Mark Antony, Octavian (the future Emperor Augustus), and others fought for supremacy in shifting alliances that tested the stability of the entire Mediterranean. Horace found himself caught up in these events: upon hearing of the power struggles in Rome, he left Athens and sided with Marcus Junius Brutus—the leader of the conspiracy to assassinate Caesar. Horace served as a military tribune (an officer rank), presumably commanding a Roman legion under Brutus' command.

However, Brutus and the conspirators suffered a decisive defeat at the Battle of Philippi in 42 BC, marking a major turning point not only for Rome, but for Horace personally. The poet later described himself wryly as having thrown away his shield during the battle - an ironic, self-deprecating admission of a fledgling soldier in the losing cause.

In the aftermath, Horace was pardoned by Octavian's government but found himself bereft of status and property. He returned to Rome, where necessity led him to become a scriba quaestorius (a clerk in the treasury). While this position was not the result of ambition, it did provide the financial stability Horace needed to reorient his life and begin his literary pursuits in earnest.

Patronage and the Circle of Maecenas

Central to Horace's literary career was his relationship with Gaius Cilnius Maecenas, a powerful political advisor to Augustus and an influential cultural patron. Maecenas gathered around him a group of poets - most famously Virgil, Propertius and Horace - who would help fashion a new cultural identity befitting the Augustan age.

This circle of literary figures found in Maecenas a generous supporter, and through his friendship and financial backing, they received the means to write without undue financial distraction.

Horace's introduction to Maecenas occurred around 38 BC, facilitated by friends within Rome's literary milieu. The connection proved momentous. By 33 BC, Maecenas had gifted Horace a small estate in the Sabine hills, just outside Rome, freeing him from the daily grind of urban life and state bureaucracy.

This idyllic retreat became not only a symbol of patronage but the setting for much of Horace's poetry. It was there, surrounded by rustic nature, that Horace composed works that balanced philosophical reflection with personal experience, forging a distinctive poetic voice that celebrated moderation and individual contentment.

While it is tempting to see Horace's association with the Augustan regime as purely political propaganda, his writings are more nuanced. Like Virgil's Aeneid, Horace's compositions certainly contributed to the cultural narrative of a new golden age under Augustus, but they also gave voice to personal convictions, pleasures, anxieties about philosophical questions, moral conduct, and the ephemeral nature of life.

The Satires and the Epodes

Horace's earliest published works are believed to be the two books of Satires (Sermones), composed in hexameter verse. True to Roman literary tradition, these satires adopt a conversational tone to offer social criticism, comedic anecdotes and moral observation.

Horace followed in the satirical footsteps of Gaius Lucilius (c. 180–103 BC and considered the earliest known Roman satirist, often called the "father of Roman satire"), but with a lighter, less caustic style. His satire tends to be self-reflective and conversational, directed not just at the vices of the Roman elite but also at his own foibles. Common themes include hypocrisy, avarice and the pursuit of vain ambitions. He balances critique of societal ills with an Epicurean emphasis on moderation, reason and personal happiness.

Around the same time, Horace also composed the Epodes, short poems in varying meters that owe their structure largely to the Greek iambic tradition. Often, these poems are more biting than the Satires, employing a sharper, even menacing, tone aimed at enemies both personal and societal.

Yet even in the Epodes, Horace's imagination dwells on ideas of freedom, contentment, and the unpredictability of life's fortunes. One can detect an emotional tension between his deep-seated desire for tranquility and the chaotic political environment surrounding him.

The Odes: Masterpieces of Lyric Poetry

Arguably Horace's greatest artistic achievements are found in his four books of Odes (Carmina), published in stages between roughly 23 and 13 BC. These lyric poems draw heavily from Greek models - particularly Alcaeus and Sappho - transposing the meters of the Greek lyric tradition into the Latin language.

Though Horace was not the first Roman poet to experiment with Greek meters, his consistent mastery and variety of metrical forms remain a hallmark of his craft.

Thematic Range

The Odes traverse themes as wide-ranging as love, friendship, wine, moral philosophy, the passage of time, and the nature of fame. They often merge the personal with the political, celebrating the peace brought by Augustus' regime, while also advising moderation and humility.

The stylistic hallmarks - technical elegance, rhythmic sophistication, and a polished but sincere emotional register - won Horace admiration among contemporaries and successive generations.

Carpe Diem

One of Horace's most famous thematic motifs is the exhortation to "seize the day" ("carpe diem"). This phrase, drawn from Ode 1.11, has become a cultural byword for living in the present, fully aware of life's brevity and uncertainties.

Contrary to some modern interpretations that read it as a simple hedonistic cry, "seize the day" in Horace's poetry typically sits alongside reminders about self-restraint and moral clarity. The fleeting nature of life, for Horace, justifies neither despair nor reckless indulgence, but rather a reasoned enjoyment of the moment, guided by friendship and virtue.

National Pride and Religious Sentiment

The Odes also contain poems composed for public occasions and ceremonies. In these, Horace extols Augustus' achievements, celebrates the Augustan vision of renewed piety, and reflects on Rome's destiny. While partly fulfilling his role as a poet patronized by the regime, Horace typically embeds these nationalistic themes in broader reflections on religious and moral ideals.

The Odes thus often shift seamlessly between personal introspection and communal celebration, a stylistic duality emblematic of Horace's poetic genius.

The Carmen Saeculare

In 17 BC, Augustus planned a lavish celebration called the Ludi Saeculares (Secular Games), intended to mark the beginning of a new age under his rule. As part of these festivities, Horace was commissioned to write a hymn, the Carmen Saeculare, to be performed by a chorus.

The poem praises Apollo and Diana, invoking them to bless Rome with fertility, moral virtue and military success. It echoes many Augustan ideals: a restoration of traditional religion, the moral renewal of Roman society, and the promise of peace after decades of civil conflict.

Though relatively brief compared to his other works, the Carmen Saeculare holds a prominent place in Horace's oeuvre because it demonstrates the poet's capacity to blend ceremonial grandeur with a polished, lyrical style. The poem also underscores his importance within the cultural program of the Augustan regime; by commissioning Horace for a major public event, Augustus and Maecenas made him a key voice of the new order.

The Epistles and Later Works

As Horace aged, his poetic style shifted somewhat. The two books of Epistles (c. 20 and 14 BC) mark a return to hexameter verse, but eschew satire's sharper edges in favor of philosophical letters. These epistles were addressed to friends, acquaintances and, in some instances, to Augustus himself.

In them, Horace explores themes of moral philosophy, literary criticism, and the daily habits that foster a balanced life. For example, the famous Epistle to the Pisones - commonly known as the Ars Poetica - lays out his views on literary theory and aesthetic judgment. Though the Ars Poetica might not present a systematic poetics per se, it contains aphoristic advice on style, genre, and the writer's craft that would prove enormously influential on Renaissance and Neoclassical literary thought.

By the time Horace published his second book of Epistles, he had secured his place as a figure of significant cultural authority. He had become not merely a poet but an arbiter of taste and morality, dispensing insights from a perspective shaped by an intimate association with political power, yet tempered by an Epicurean philosophy that valued independence, humility, and the everyday joys of rural retirement.

Literary Style and Innovation

Horace's stylistic achievements can be grouped into several key areas:

1. Metrical Experimentation: He successfully transplanted Greek lyric meters into Latin. The Alcaic and Sapphic stanzas, among others, became vehicles for Roman expression. This required a refined skill in adapting the flexibility of Greek verse to the more rigid accentual patterns of Latin.

2. Fusion of Greek and Roman Themes: While indebted to Greek motifs, Horace's poetry is profoundly Roman in its moral perspective, social commentary and reverence for tradition. He was adept at turning Greek myths and gods into allegorical or symbolic references for Roman audiences.

3. Conversational Tone: Even in his more formal works, Horace cultivated a direct, personal voice. His satires and epistles engage readers as if in dialogue, a trait that sets him apart from poets who adopted grand or epic tones.

4. Moral and Philosophical Underpinnings: He wove Epicurean philosophy - emphasizing moderation, friendship and avoidance of anxiety - into his verse, creating a literary persona that was worldly but contemplative, ironical yet sincere.

This delicate balance of technical virtuosity, philosophical insight and personal warmth assured Horace's place in the Roman literary canon. His poems combine a cultivated elegance with universal reflections, making them adaptable to countless reinterpretations across the centuries.

Critical Reception and Influence

Horace's stature began rising significantly in his own lifetime. By the time of his death in 8 BC, he was regarded as a major literary figure. Subsequent generations, particularly under later Roman emperors, continued to read and imitate his works. During the Middle Ages, Horace's texts were studied in monastic schools as part of the classical curriculum.

Moral allegorists, somewhat at odds with certain secular or erotic elements, nonetheless found in his poems a trove of maxims regarding human nature and ethics.

By the Renaissance period, Horace had become a central figure in the revival of classical learning. Italian humanists praised his stylistic clarity, and the Ars Poetica especially influenced debates about genre, poetic decorum and unity of structure.

Across Europe, from the courts of France to Elizabethan England, Horatian principles of moderation and polished craftsmanship shaped the aspirations of poets. Figures like Ben Jonson and Alexander Pope in England, and later the German poet Johann Wolfgang von Goethe, counted Horace among their major inspirations.

Moreover, Horace's famous injunctions – "carpe diem" ("seize the day") (Odes 1.11) and "aurea mediocritas" ("the golden mean") (Odes 2.10) - became succinct expressions of Western cultural values, repeated in essays, sermons and songs.

His phrase "dulce et decorum est pro patria mori" ("It is sweet and fitting to die for one's country") (Odes 3.2), originally an exhortation to Roman martial virtue, was famously subverted by the English war poet Wilfred Owen in the context of World War I, demonstrating Horace's lasting capacity to provoke commentary, whether in agreement or in stark critique.

Philosophical Undercurrents: Epicureanism and Moderation

A recurring question in Horatian scholarship concerns his philosophical leaning. While Horace does not expound systematic doctrine, his works echo key Epicurean tenets. The poetry underscores the values of friendship, the fleeting nature of life, and the pursuit of tranquility (ataraxia).

In his discussions of wealth, ambition and success, Horace wields a gentle but insistent reminder that these pursuits often lead to anxiety, envy, or worse. His answer lies in balanced living: enough property to live without want, enough ambition to excel but not be consumed, enough love to enjoy companionship without sinking into destructive passion. Such an approach allowed him to navigate the political labyrinth of the Augustan court while retaining his sense of poetic autonomy.

Horace's Personal Legacy and Death

Horace never married and left no descendants. His final years were spent in the quietude of his Sabine farm or in Rome. He remained close to Maecenas, who also died in 8 BC. According to tradition, Maecenas's last words to Augustus included the plea to "Remember Horatius Flaccus as you would me." Horace, too, died that same year, barely a few weeks after Maecenas. Buried on the Esquiline Hill near his benefactor, Horace's remains rest in the city he celebrated and critiqued with such deft eloquence.

The poet's personal legacy, from his humble origin to his triumphant literary career, is a testament to the social fluidity and cultural vibrancy of the late Republic and early Principate. With a freedman for a father and a failing civil war behind him, Horace was nonetheless able to ascend to one of the highest rungs of Rome's literary pantheon. His life story remains an illustrative example of how talent, patronage and historical circumstance converged to produce a poet of singular voice.

The Enduring Appeal of Horace

Across the centuries, Horace's work has never fallen entirely out of fashion. His voice, at once urbane and heartfelt, speaks to universal human experiences - love and loss, the desire for tranquility, and the unsettling reality of life's impermanence. He deftly married the Greek lyric tradition to the cadence and sensibility of Latin, forging a body of poetry that was both richly classical and distinctly Roman.

Furthermore, his willingness to explore personal flaws, to laugh at human vanity, and to remind readers of mortality fosters a sense of direct connection. Many readers today find his meditations on life every bit as relevant as they were in the first century BC.

Horace's verses offer a balanced worldview. He acknowledges the fragility of political fortunes, the limitations of human aspiration, and the terror of the unknown. Yet he also rejoices in small pleasures—wine, friendship, a warm countryside retreat, the beauty of a sudden spring etc. His calls for moderation resonate especially in an age buffeted by extremes.

In surveying Horace's life, from his Apulian birthplace to his service in civil war, from the acclaim of Maecenas's circle to the quiet reflections of the Epistles, one sees a poet intimately shaped by the turbulence of his era. That he chose to channel that turbulence into refined lyric craft, refined moral contemplations, and a gentle wit is a credit to his sensibilities. Whether found in a battered school text or on the shelves of a grand library, the words of Quintus Horatius Flaccus endure because they speak to deep-seated human longings: for wisdom, peace, and the fleeting but transcendent joys of the present moment.

In this respect, Horace stands as a bridge between the ancient world and our own, a voice that reminds us of life's precariousness and its everyday wonders. The centuries have changed empires and languages, but his counsel remains: Embrace the here and now with a clear heart, but do so wisely, with humility, gratitude, and an open mind.

Two millennia later, we can still learn much from this voice out of Rome's golden age - a poet whose elegant lines continue to inform our understanding of what it means to live fully, responsibly, and joyously.

Works: