Reviewed By: Michael Mates

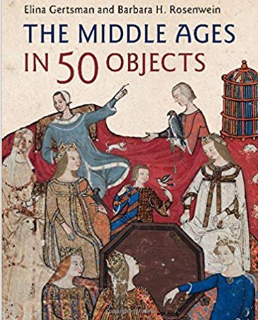

Yes, you can judge a book by its cover. The cover of this book (actually a dustjacket) shows a sour-faced woman, whose plain dress contrasts with the upholstered luxury of the six women and a boy sitting at their graceful ease in Lemon Face's equally luxurious bedchamber.

What will the authors, two expert docents leading us on a museum tour, say about this scene in the few pages allotted for each of the 50 objects? Quite a bit, as it turns out, as they follow the method of analysis used for all of them: display the splendid sumptuousness of the exhibits, elicit the beauty and artisanal skill seen in each one, and then move outward into the social, cultural, political, historical and religious contexts. We even get maps, to refresh our rusty knowledge of where Khurasan, the Diocese of Lièges, Venetian territories, and other centres of power and aesthetics were located.

So, back to the dust-jacket portrait (pp 80-83): its medium is ink, tempera and gold on vellum, and its subject, from a 14th-c Genoan Treatise on the Vices, is Acedia (Sloth). The diversions (birds, dogs, dice, beautifully coiffed women) are many, and the "surroundings are exotic, drawn from the artist's intimate knowledge of the Islamic world and its artistic traditions" (p 80). A discussion of trade with the Mongol Empire (map included), the loss of Crusader states, and the dangers of Sloth to the "virtuous [Christian] merchant" (p 82), is followed by Dante's portrayal of the slothful, in the contemporary Divine Comedy: the penitent slothful in Purgatory, and the unlucky slothful in Hell (p 83). The essay concludes with a meditation on the Mediaeval view of the nature and effects of Sloth, the opposite of Charity, which was the highest good.

From the 50 objects described in the book, my choice for pure barbaric splendor, luxury and mechanical cleverness is the 14th-century Parisian table fountain, made of gilt silver and enamel, with spinning wheels and tinkling bells spurred into action by jets of water. The authors' usual erudite discussion covers Mediaeval automata, Islamic influences, and poets who "extolled fountains as simultaneously perilous and alluring" (p 149).

And there is more, a great deal more, in this treat for the eyes and stimulus to understanding. Fascinating nuggets include Islamic calligraphy and Kufic script (pp 26-29), the "holy theft" of relics (p 33), how to sing neumes (p 52), a table of consanguinity (p 164), and the splendidly dangerous-sounding Frankish dagger called the scramasax (p 164). All in all, a fitting tribute to the alluring polychromatic skills and beauty of Mediaeval art - the objects that delighted the senses and haunted the imaginations of their creators and consumers.

The book is a perfect gift, and, as an added bonus for those of us in North America, the objects are all within driving distance, at 11150 East Blvd., Cleveland, Ohio, home of the Cleveland Museum of Art. That's a 36-hour, 2,433-mile drive from where I live.

Michael Mates is a retired U.S. Foreign Service Officer who reads and gardens in Monroe, Washington State.

About The Book

The extraordinary array of images included in this volume reveals the full and rich history of the Middle Ages. Exploring material objects from the European, Byzantine and Islamic worlds, the book casts a new light on the cultures that formed them, each culture illuminated by its treasures.

The objects are divided among four topics: The Holy and the Faithful; The Sinful and the Spectral; Daily Life and Its Fictions, and Death and Its Aftermath. Each section is organized chronologically, and every object is accompanied by a penetrating essay that focuses on its visual and cultural significance within the wider context in which the object was made and used. Spot maps add yet another way to visualize and consider the significance of the objects and the history that they reveal.

Lavishly illustrated, this is an appealing and original guide to the cultural history of the Middle Ages.

Click Here for More and to Purchase