This article was contributed to UNRV by Timetravelrome - an app dedicated to the Ancient Roman Empire. Find out about this app on www.timetravelrome.com or download it on Appstore or Playstore.

PantheonRome.jpg by Deensel is licensed under CC BY 2.0

"For the more he surpassed others in excellence, the more inferior he kept himself of his own free will to the emperor; and while he devoted all the wisdom and valour he himself possessed to the highest interests of Augustus, he lavished all the honour and influence he received from him upon benefactions to others."

- Cassius Dio about Marcus Agrippa

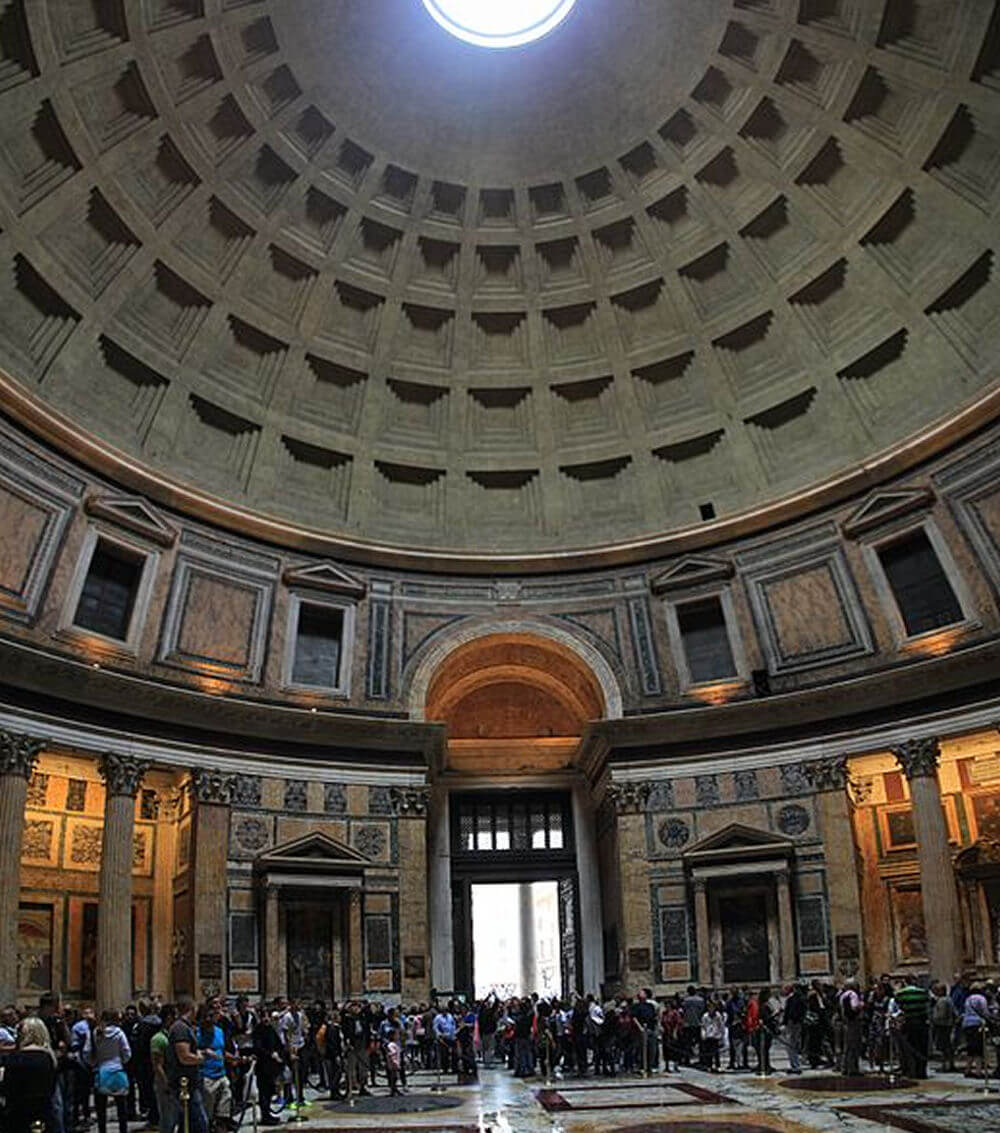

The magnificent Pantheon towers above what was once ancient Rome's Campus Martius. It is among the best-preserved ancient structures in the world today, kept safe from the ravages of time by its continued use throughout the centuries and its transition into a Christian church.

Yet this monumental building bears an inscription not to a Roman emperor, but rather reads "M·AGRIPPA·L·F·COS·TERTIVM·FECIT." (M[arcus] Agrippa L[ucii] f[ilius] co[n]s[ul] tertium fecit - "Marcus Agrippa built this"). The words link the Pantheon directly to Marcus Agrippa; general, admiral, architect, and the ultimate right-hand-man of Octavian Augustus.

A Youthful Alliance

Augustus_with_Agrippa.jpg is in the Public Domain

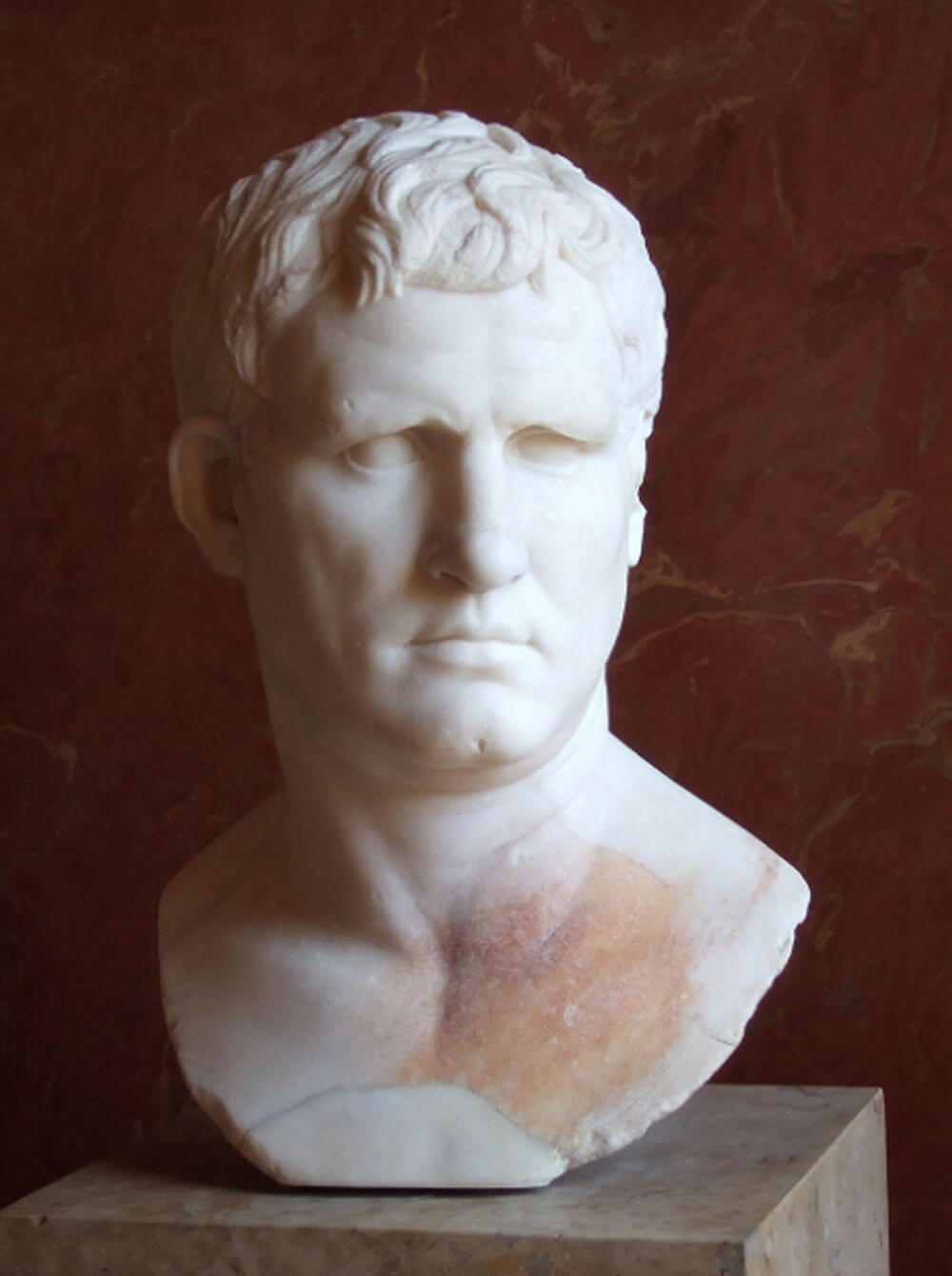

What made Agrippa different to many powerful Romans is that his rise to power came about as a consequence of his abilities, as opposed to just relying on connections or the prestige of a family name.

Agrippa came from humble origins - plebeians from the Italian countryside - something his and Octavian's opponents enjoyed pointing out in later years. Agrippa was about the same age as Octavian. After catching the eye of Julius Caesar in the campaigns against Pompey, Caesar sent the young man to be educated with Octavian in Apollonia.

There, Octavian and Agrippa grew to be close friends, along with another young student, Quintus Salvidienus Rufus. Yet Salvidienus would eventually offer to betray Octavian, while Agrippa remained steadfastly loyal.

Four months after their arrival, news came that Julius Caesar had been assassinated, and Octavian learned that he had been adopted as Caesar's son and heir. In the years that followed, Agrippa remained by Octavian's side during the campaigns against Caesar's assassins and the ordering of Rome with Mark Antony and Lepidus.

Agrippa became indispensable to Octavian. He governed Rome and defended against Sextus Pompey, put down revolts in Gaul and successfully fought the Germanic tribes, and eventually lead Octavian's navy to a decisive victory over Sextus Pompey's fleet at Mylae and Naulochus.

His skills as an admiral again came to bear in the final confrontation with Mark Antony and his new ally, Cleopatra. Largely thanks to Agrippa, Octavian won the Battle of Actium, leading to the ultimate defeat of the couple and Octavian's rise to power in Rome as Augustus.

Agrippa and the Pantheon

Pantheon_inside.jpg by Erin Silversmith is licensed under GNU Free Documentation License, version 1.2

Agrippa soon proved himself as useful as a civil assistant as he had been a military one. He threw himself into renovations and improvements of Rome. As the first ever water commissioner of Rome, he improved the city's sewer system, built baths, and expanded the Aqua Marcia aqueduct to supply fresh water to all classes of citizens.

He also invested large quantities of his own money into building works; funding public gardens, temples, a gymnasium, art exhibitions, and the great Pantheon itself.

Sadly, the Pantheon that survives today is not the one built by Agrippa, but rather a reconstruction built under Trajan and Hadrian after fire destroyed the original.

The only currently known contemporary information comes from Pliny the Elder, who recorded that the structure was decorated by Diogenes of Athens. He particularly remarked upon the Caryatides, female statues which formed the temple columns, and statues which lined the roof, all of which were "looked upon as master-pieces of excellence." The capitals of the pillars were apparently made of Syracusan bronze.

The layout of the original building remains the subject of debate, though many historians and archeologists believe that it closely mirrored the surviving Pantheon, without the domed ceiling.

Marcus_agrippa_louvre_portrait.jpg is licensed under CC BY-SA 3.0

As a testament to the deep bond between Agrippa and Augustus, Agrippa initially wished to name the building the Augusteum, and to place a statue of Augustus in the center of the main chamber. However, Augustus refused both of these honors, conscious of his shaky political position.

Agrippa instead placed a statue of Julius Caesar in prominence in the inner chamber, and statues of himself and Augustus in the antechamber, flanking the entrance.

Cassius Dio writes that: "This was done, not out of any rivalry or ambition on Agrippa's part to make himself equal to Augustus, but from his hearty loyalty to him... Augustus, so far from censuring him for it, honoured him the more."

Indeed Augustus elevated Agrippa higher and higher, both privately and politically.

Friendship and Loyalty

Augustus suffered from poor health, and from early on in his rule he established Agrippa as his heir. However, as they were the same age, Agrippa was not an ideal option as an heir. As a result, Augustus brought Agrippa officially into his family by giving Agrippa the hand of his daughter, Julia, in marriage. When the couple produced two boys, Augustus officially adopted the boys, ensuring his line of succession.

Meanwhile, he granted significant political powers and honors to Agrippa, to the point that Agrippa shared equal power with him in everything but seniority. Although he held massive political power and the loyalty of the legions, Agrippa never challenged Augustus. He remained fiercely loyal, and proved himself a true friend. Cassius Dio called him "the noblest of the men of his day."

In his later years, Agrippa began to suffer from illness and pain, now believed to have been gout. He carefully concealed it from his friend, not wishing to be a burden or embarrassment by way of infirmity.

A Difficult Farewell

Agrippa_memorial_coin.jpg by Classical Numismatic Group, Inc. is licensed under CC BY-SA 3.0

While returning from a campaign in Pannonia in 12 BC, Agrippa fell desperately ill, though it is not known whether this was related to his previous illness or not. When word reached Augustus, he rushed to reach his friend's side, even leaving in the middle of an official festival. Yet, by the time he arrived, Agrippa was already dead.

Devastated, Augustus personally saw to funeral arrangements, and presided over the ceremony himself. Although Agrippa had built a building to be his tomb, Augustus instead placed the ashes of his closest friend inside his own personal mausoleum, and insisted that a carving of Agrippa be added to those of his family members included in the structure.

He further commemorated Agrippa through gladiatorial games held in his honor, and the commissioning of a number of special coins depicting him. One even portrays Augustus crowning Agrippa with a star, a touching witness of their brotherly friendship, and one which remains to this day.

What to See Here

Pantheon_(Rome).jpg by BjoernEisbaer is licensed under CC BY-SA 3.0

Augustus' right-hand man, Marcus Agrippa, built the original Pantheon sometime after the Battle of Actium in 31 BC. Even in antiquity there was some controversy around its name. Literally meaning, "honour all gods" in Greek, we know that Agrippa's building did indeed display the statues of many Roman gods, including those of Mars and Venus.

However, the third century AD historian Cassius Dio also suggests that it could have been given its name because the temple's iconic vaulted roof resembled the heavens.

As stated earlier, what stands today is not the original Pantheon. Agrippa's Pantheon was destroyed in the fire of 80 AD (some 37 years before Hadrian ascended to the throne) and anything that survives is most likely subsumed within the current building. Being the good emperor that he was, though, Hadrian chose to play modest and kept the old inscription.

While Hadrian's good, modest side shone out in the building's construction, so too did his cruel side. The emperor famously executed the Pantheon's Greek architect, Apollodorus of Damascus, over an argument about the structure.

The exterior façade and vaulted ceiling are the only relics of the Pantheon's ancient past. That said, having mysteriously survived the barbarian raids that proved devastating for many of the city's other architectural wonders, the Pantheon is ancient Rome's best-preserved monument.

The Christians transformed it into a church in 609 AD, and indeed it still functions as one: St Mary of the Martyrs.

It is also the final resting place of Italian kings, poets and the artist Raphael. Plus, some 2,000 years after its construction, the Pantheon can still claim to have the world's largest unsupported dome.

Further Reading

If you are interested in learning more, check out Lindsay Powell's in-depth biography "Marcus Agrippa".

Sources

- Cassius Dio, Roman History

- Tacitus, The Annals

- Pliny the Elder, Natural History

- Suetonius, Life of Augustus